- Dick Oskam

- Global Head Transaction Services Sales, ING

- Eleanor Hill

- Editorial Consultant, Treasury Management International (TMI)

The Case for On-Behalf-Of Structures

The trend towards treasury centralisation is once again picking up pace among corporates as they look to optimise visibility, efficiency, and control in a fast changing, increasingly challenging global business environment. In a recent conversation with TMI, Dick Oskam, Global Head Transaction Services Sales, ING, considered some of the key drivers for centralisation and the solutions available to treasurers with a special focus on on-behalf-of structures.

Eleanor Hill, Editor, TMI (EH): Looking at the latest trends in cash and liquidity management, we see many clients continuing their centralisation journey. Are there any specific topics relating to this that stand out for you or perhaps are being raised by ING clients?

Dick Oskam, Global Head Transaction Services Sales, ING (DO): Broadly speaking, the key areas of concern to our clients for cash and liquidity management are:

- Real-time cash management

- APIs

- ISO 20022 migration

- Operational simplification

- Improving cash efficiency

More specifically, we have seen a shift in treasurers’ priorities when it comes to liquidity management. Covid-19, the ongoing geopolitical tension following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and supply chain disruptions of recent years have all been major factors in this rethink.

The first impact of such overwhelming events is often on corporates’ payments and liquidity management business and the respective cash flow. Mitigating the adverse impact on such fundamental aspects of a corporate is critical, yet we still see many corporates struggling to obtain clarity on their cash position. The main reasons for this, in our view, are: a decentralised treasury set-up; a scattered ERP/TMS landscape; and an inefficient account structure without cash pools.

What stands out in our discussions with clients looking to get a proper handle on these challenges is their great interest in our thoughts on simplification and increased cash efficiency of their cash and liquidity management structures. We often receive requests from clients for a ‘clean-sheet exercise’. Here, on the basis of our own knowledge of their company and its organisational set-up, the clients are interested to know how we would advise them on a redesign of their cash management structure pretty much from scratch. These clean-sheet exercises are undertaken without considering their existing structures.

These are very open sessions that are highly valued by our clients. What we often encounter through them is that many corporates have a lot of opportunity to rationalise their account structure and set up truly centralised cash pools that aggregate balances at a central location. However, legacy issues are one of the most common drags on their existing structures in pushing such initiatives through, especially with acquisitive companies.

Importantly, such a clean-sheet exercise also allows for a discussion around setting up an on-behalf-of structure.

EH: For those readers who aren’t familiar, could you elaborate what an on-behalf-of structure exactly is?

DO: Certainly. There are two types of on-behalf-of [OBO] structures: payments on-behalf-of [POBO] and collections-on-behalf-of [COBO]. POBO focuses on a company’s purchase-to-pay [P2P] process while COBO relates to the order-to-cash process.

To illustrate how they work, imagine you are buying a new laptop but I would pay your invoice for that laptop. Here, I would make a payment-on-behalf-of you. That means that the beneficiary will not see your name and account in its bank statement but mine. This would also mean that you would owe me the amount for the laptop.

COBO works the other way around. So, if you sold your laptop, I would collect the receivable.

You can see also such a set-up operating in the corporate world with, for example, a specific entity handling payment of all procurement invoices for entities in a certain business line or geography. Such an arrangement results in a more straightforward operation whereby a company potentially could use a single account to perform payments for many other entities.

EH: What kind of clients are most interested in centralisation and specifically in setting up an OBO structure? Is there a typical size or sector when it comes to the client profile?

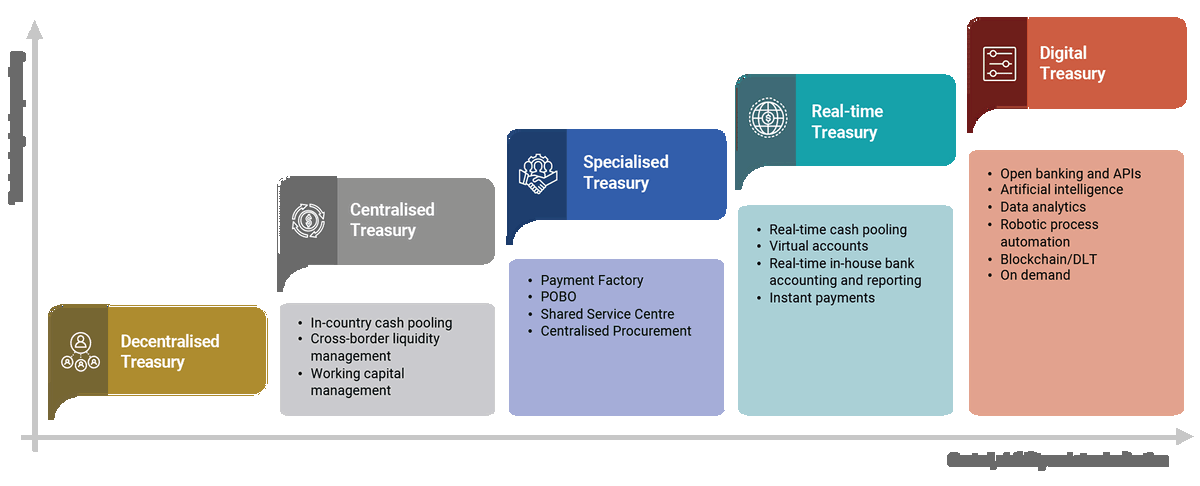

DO: This is mostly driven by the maturity of the corporate treasury. If we take a textbook example, one can divide treasuries into five different categories ranging from a decentralised treasury that has local operations and processes, to a fully digitised treasury that is characterised by seamless central digital processes, integrated data flow between treasury, business units and third-party solution providers [see Fig 1 below].

FIG 1: The future digital and strategic treasurer is expecting a seamless and real-time execution of liquidity management

We often see already centralised clients that want to enter into a discussion about further optimising treasury through setting up an OBO structure. These companies tend to already be rather centralised with a cross-border cash pool set up across multiple countries and are quite sophisticated in their cash management set-up. They are also very interested in improving their P2P and or O2C [order-to-cash] processes, bringing additional operational efficiencies.

However, in these clean-sheet exercises, OBO is also discussed as a leap towards an optimised and centralised treasury.

It is important to note that setting up an OBO structure is mostly internally driven and not enforced by external stakeholders or market developments, which tends to be the case with, for example, APIs or instant payments.

We also see that with while OBO is not industry or sector driven, companies tend to start with a certain business unit or geography (often in a single currency) for the initial roll-out of the OBO setup. We also see structures put in place for a single country.

EH: What is the value of setting up an OBO structure for a corporate treasury?

DO: There are many benefits and they can vary in their nature from company to company. Broadly speaking, there are three main drivers:

- Reduced operational complexity: This results from the shift away from many local processes towards one centralised process. You can imagine what the resulting impact on treasury could be as STP rates would increase and there would be fewer accounts to manage. It also means potentially fewer banking partners, meaning higher volumes per bank, and potentially lower banking and FX charges. In our experience, a centralised payment process also helps reduce fraud cases for corporates because there is increased central control and fewer parties are involved.

- Improved cash visibility and control: This results from payment/collection processes and flows being centralised at one location/account/entity. This will have a positive effect on the predictability of flows and will lead to improved cash flow forecasting. It also makes reporting easier for regulatory purposes because all transactions are centralised.

- Improved supply chain management and cost negotiation: These flow from procurement being more centrally managed – which in itself often results in higher volumes. The centralisation of volumes also potentially means that alternative financing through supply chain finance becomes a viable option.

At ING we see that clients often start thinking of OBO structures in combination with a payment factory or the set-up of an in-house bank [IHB]. The reason for this is that the OBO structure results in the creation of intercompany loans. Through the set-up of a netting mechanism only the net position of all intercompany loans is settled at a pre-agreed settlement date. This often results in the establishment of an IHB.

An IHB is a single entity that caters for all of the underlying operating companies’ financial transactions. Financial responsibilities such as funding and risk are transferred from local operating companies to a central treasury that has a better overview and is better equipped to deal with these responsibilities.

EH: Sounds like the holy grail – yet it seems a little too easy. Are there any challenges that companies need to be aware of?

DO: A valid question and one perhaps best answered by looking at it all in context. If we consider Europe, we often assume that the introduction of SEPA [The Single Euro Payments Area] has solved all our problems. However, due to differences in local regulations, there are still many aspects that make its implementation more complex.

In our conversations with clients, we often highlight three areas that are important when implementing an OBO structure: operational feasibility; the legal impact; and the tax implications. Consideration of these three key areas, however, will vary from country to country, even within the SEPA region, as every country has different regulations. As these regulatory requirements are an essential part of setting up a cross-border OBO structure, and companies need to be aware of their importance, they can make the set-up of an OBO structure a complex journey.

For example, in many SEPA countries taxes need to be paid or received locally through a domestic bank account often in the name of the tax-paying entity. This means that in some countries the need for a local bank account remains, nevertheless the main OBO benefit is retained as the majority of payments can be routed through an offshore POBO account.

The implementation of an OBO structure must always be customised specifically for the organisation and geared towards the corporate’s treasury set-up and footprint. Therefore, at ING we have developed an extensive bank of OBO research for 30 countries in Europe that focuses explicitly on the feasibility of setting up an OBO structure. Based on this extensive research we have a view on the operational aspects, and the legal and tax implications of OBO, on a country-by-country basis.

From feedback, we know clients value the intelligence we have at hand as a great basis for their own internal discussions about OBO and developing a good view on the possibilities and opportunities. Nevertheless, corporates need to consult with their tax and legal adviser before putting anything in place.

EH: How can companies realise the OBO benefits to the maximum? Are there specific steps they need to take?

DO: First and foremost, it is important to understand that setting up an OBO structure is not a one-size-fits-all solution. It all starts with building a business case that includes what the benefits will be after the implementation in terms of operations, costs, fraud reductions, improved working capital and so on.

Thereafter a thorough assessment of the tax, legal and regulatory requirements of the countries and business units in scope needs to be made.

There are some common lessons learnt that we have encountered frequently. First, the importance of a mandated buy-in for the initiative from senior management is critical. At ING we have often seen OBO implementation processes endorsed by senior management have a higher chance of success.

Second, beware of resistance to change within the organisation. Local staff might be afraid to lose responsibilities and the control over local cash. Cultural differences within the organisation and treasury set-up can also be a major challenge. Localised support is essential for success, so taking the time to explain to local teams why it will also benefit them is critical.

And last but not least, make sure to define a realistic roadmap and timelines. We always recommend starting small, i.e. setting up POBO for one country and then gradually expanding. Why POBO? Simply because as this is initiated by the corporate itself, it lends itself to greater control of the process in those vital early stages.

Finally, always bear in mind that there is a high chance you will experience delays due to corporate activity such as acquisitions and leadership changes, and external factors such as pandemics, geopolitics and supply chain disruptions.

EH: Some excellent advice there for treasurers, thank you. Are there any final points you would like to briefly highlight to sum up our conversation?

DO: As discussed, corporates can simplify their treasury operations through implementing an OBO set-up that will centralise payments and bring increased control and visibility over cash and potential cost savings.

More often than not, the types of companies that will pursue OBO implementation will already have a substantial level of centralisation. Their aim will be to further reduce treasury complexity and enable it to become a centre of expertise.

Despite the clear potential benefits, it is important to remember that setting up an OBO structure will have an impact on a company’s internal processes and will consume resources to fully embed.

Last, it must be recognised that an OBO journey is not a straightforward implementation but a bespoke solution that calls for reliable advisory services around feasibility, and a banking partner that is experienced in successfully setting up these structures.