- Eleanor Hill

- Editorial Consultant, Treasury Management International (TMI)

China is now home to the world’s second largest bond market – an interesting potential source of yield and diversification for both global and local investors. With growing opportunities in Chinese fixed income markets, however, comes greater risk. Proper due diligence and rigorous analysis of issuers are critical for understanding the true risk characteristics of onshore credit investments, so that investors may take advantage of the growing market opportunities while minimising risk.

Growing investment opportunities and challenges

China has undergone remarkable economic growth over the past two decades, helped by rapid industrialisation and swiftly developing domestic markets. Underpinning this growth have been China’s fixed income markets, which have seen a massive increase in size and scope.

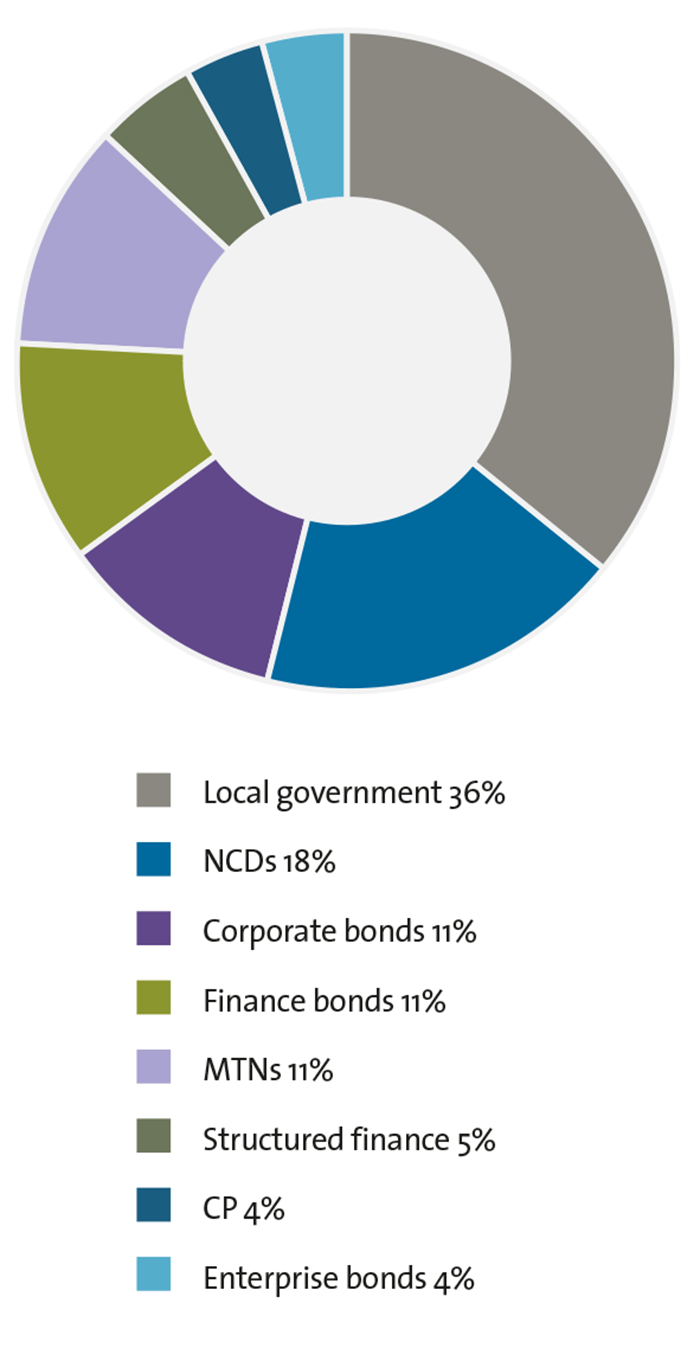

Fig 1: China Credit Market Issuer Mix

Source: J.P. Morgan Asset Management; information as at 30 June 2019.

A period of interest rate liberalisation, part of fundamental financial reform undertaken during the past decade, combined with rapid financial market innovation, has increased the number of investors seeking market-driven yields, the range of Chinese corporate issuers (fig. 1) seeking funding and the variety of instruments available (fig. 2). Together, these forces have precipitated a twelvefold surge in the size of China’s onshore credit market, contributing to the depth, liquidity and vigour of the Chinese bond market today.

Alongside the significant growth in the Chinese onshore bond market, however, the risks of investing have also increased. The government’s implicit guarantee has been largely eliminated (see box 1). The credit fundamentals of some corporate issuers are weak. And domestic rating agencies’ methodologies have limitations. Together, these issues are creating significant challenges for credit analysis.

The challenges of investing in the onshore credit markets are magnified by a lack of experienced credit analysts, weak corporate governance and limited financial disclosures. In addition, underdeveloped bankruptcy laws, opaque financial links, the scarcity of cross-default clauses and limited rating actions by domestic rating agencies constrain investors’ ability to ascertain whether a default has actually occurred or what the likely recovery terms or ratios might be.

The picture is further complicated by the fact that until recently, none of the major international rating agencies (Fitch, Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s) had licences to operate in China. Nine local rating agencies dominate onshore rating. The Chinese authorities regulate the number of rating agencies and rating nomenclature. By law, bond issuers are only required to have one rating, making competition among domestic agencies intense. Operating independently from international market standards and practices, local rating agencies have developed their own methodologies, limiting investors’ ability to map local ratings to international rating scales.

This is now changing, with some international rating agencies having received licences to issue onshore credit ratings in China. While they will face the same regulatory and data quality challenges as their local peers, their entry marks a significant and positive development. Their strong reputations and rigorous rating methodologies should increase international investors’ confidence while boosting the professionalism of the domestic credit rating industry.

Against this backdrop, how can investors take advantage of China’s onshore bond market, while minimising downside risks?

Fig 2: The wide variety of Chinese credit instruments

Source: J.P. Morgan Asset Management; information as at 30 June 2019.

Due diligence and analysis

Given the complexity of China’s onshore bond markets, and the recent escalation of credit risks, the importance of due diligence and rigorous, independent analysis should not be underestimated. To balance the risks and returns of investing in China’s corporate bond markets, a sound investment policy will be required.

Multinational corporations operating in China should ensure that their global (or US-centric) investment polices take account of local market characteristics, instruments and practices. Meanwhile, local corporations should create or update their investment polices to prepare them to successfully navigate developing domestic markets, rapidly changing regulations and evolving business requirements.

The need for capital preservation should help limit the list of eligible securities – which may include instruments such as exchange-traded repurchase agreements, structured deposits and alternatives such as money market funds and separately managed accounts. The investment policy should also help ensure adequate liquidity by outlining suitable concentration and tenor limits for various sectors, credit ratings and issuers, while reflecting the size and availability of local investment options.

Most investment policies will also require achieving competitive returns; this will determine the lowest acceptable credit rating and longest acceptable maturity. In China, that means considering the sovereign ceiling, and both the international and domestic rating scales.

Independent credit research

As well as a sound investment policy, independent credit research is vital. Until recently, investors in China’s fixed income securities conducted little credit research beyond a basic screening of sector, rating or the credit spread to Chinese government bonds – largely due to the implicit government guarantee (now largely removed as per box 1).

The ultimate goal of credit research is to ascertain the willingness and ability of a borrower to repay a debt. For cash investors focused on liquidity and security, avoiding rating downgrades and defaults is a key priority. Therefore, Chinese credit issuers should be assessed on their standalone capital, asset quality, management, earnings and liquidity. In addition, industry and operating trends provide valuable context, and an issuers’ access to collateral and alternative funding sources is also important.

Box 1: Goodbye to the implicit government guarantee

For the first 65 years after the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the local financial markets never witnessed a default, nor did an investor suffer a loss due to the nonpayment of a loan. Loss-making organisations at risk of reneging on their debts were either bailed out or taken over at the behest of the government. This practice reinforced the widespread belief that corporate debts in China are underwritten by an implicit government guarantee.

That changed in March 2014, when China’s fixed income market suffered its first-ever bond default. Subsequently, the pace and size of bond defaults has increased – especially as tighter liquidity conditions, and new rules designed to curtail the shadow banking sector, placed additional financial pressure on lower-quality corporate issuers and smaller regional banks.

Meanwhile, in April 2015, the Chinese government introduced a deposit insurance scheme, limiting deposit protection to CNY 500,000 per bank account. Both these factors significantly eroded confidence in the implicit government guarantee and magnified the challenges of investing in the onshore credit markets.

While the frequency of reporting and level of detail published by Chinese bond issuers has improved significantly, several credit research challenges remain. These include accounting practices that differ from international accounting standards and a lack of clarity around certain items on many company financial statements. These idiosyncrasies highlight the need for investors to create well-designed credit guidelines and utilise independent and experienced credit analysts.

The China Securities Regulatory Commission’s (CSRC) oversight of money market funds and asset management products are now more directed towards risk and liquidity issues, and provides a basic risk framework for these investments. Nevertheless, the limitations of domestic credit ratings can leave investors exposed to significantly more risk than expected. In contrast, onshore investment products with triple-A ratings assigned by international rating agencies offer higher levels of security and liquidity, as they are based on international rating systems and methodologies.

In addition to the above steps, assessing the potential level of government support is also important when evaluating Chinese onshore bond investments. As explained above, state-owned entities should no longer be considered state-guaranteed.

Nevertheless, organisations and corporations that are systemically important and linked to the central government are more likely to receive support during periods of financial stress than regional or city-owned entities. In those cases, the willingness and ability of the potential guarantor to offer support may be limited. Investors should assume that for private companies, little or no government support is likely to be forthcoming.

Accessing new opportunities

In conclusion, the Chinese corporate bond market continues to grow in size and importance and is now too large for global cash investors to overlook. The rapid increase in the range of issuers and instruments offers investors significant diversification and yield benefits, yet also poses the significant challenge of understanding and identifying credit risks.

Rigorous analysis of issuers and counterparties is critical to understanding the true underlying risk characteristics of onshore credit investments. A robust investment policy, combined with independent credit research and an objective analysis of the potential level of government support to issuers, are critical steps that can minimise downside risks while allowing cash investors to take advantage of this important, new market opportunity.

This article is an edited version of a paper written by J.P. Morgan Asset Management. To read the full report, visit jpmorgan.com/chinamoneymarket