After the Ballots

How the ‘year of elections’ reshaped treasury priorities

Published: January 01, 2000

Implementation of the new bank regulation will change the pricing companies can expect on some deposits and could result in changes to, or discontinuation of, some products altogether. Consequently, organisations need to re-examine their investment policies to take account of this new market environment.

The experience of the financial crisis rightly left an indelible mark on the minds of corporate treasurers. Increased counterparty risk led to changes in the banks that companies worked with: security and liquidity became paramount, with yield trailing a distant third as a priority.

Now, however, the liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) under Basel III will prompt companies to reassess their investment policies and how they evaluate risk. While Basel III, which was developed by the Bank of International Settlements in the wake of the financial crisis, primarily targets financial institutions (FIs), it is expected to have far-reaching implications for corporates.

During the economic crisis a number of financial firms failed for any number of reasons, but the issues were largely manifested in a lack of short-term liquidity. To prevent this in the future, Basel III introduces liquidity requirements, designed to improve banks’ stability in the event of a stress event, by ensuring that they have sufficient liquidity.

Basel III introduces liquidity requirements, designed to improve banks’ stability in the event of a stress event, by ensuring that they have sufficient liquidity.

In the short term, the most important of these requirements is the liquidity coverage ratio (LCR), which will be implemented beginning January 2015. The LCR will have a significant impact on corporates as it increases the cost to banks of holding clients’ deposits, which is likely to be reflected in a lower rate of return for some types of deposits.

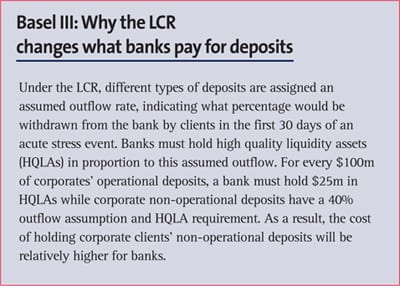

Moreover, the LCR differentiates between different types of deposits. Deposits are divided into operational and non-operational cash. Operational is tied to day-to-day working capital flows of an organisation; non-operational is generally described as excess cash and will be treated differently depending on customer type - for example, whether they are corporates or financial institutions (with further distinctions made between different types of FIs).

Different categories of deposits have different costs associated with holding them (see box for details). As a result, the rewards available on non-operational cash will change. This will need to be factored into companies’ investment policies.

The LCR is already affecting bank behaviour as it relates to some types of deposits. Operational balances tied to working capital transactions will receive the most favourable treatment under the LCR framework, and as a result corporations can expect that such balances will be more valued and sought after by banks. Conversely, deposit account balances deemed non-operational will have a higher percentage of assumed outflow and corresponding HQLAs assigned. The higher cost of holding non-operational deposits on banks’ balance sheets is expected to reduce returns available on these balances. This is the direct opposite of what corporates have been used to: in the past, operational cash earned lower rewards than non-operational cash sitting on banks’ balance sheets.

As banks alter their range of product mix in response to LCR, corporates may need to optimise their cash efficiency, gain visibility over working capital flows and effectively segregate their operational and excess cash. Pricing for term deposits (TDs) under 30 days have largely dropped to zero because such deposits are relatively less attractive to banks under the LCR, making TD pricing beyond 30 days more attractive. In addition, some banks are no longer quoting for TDs of tenors less than six months.[[[PAGE]]]

Some corporates may find that banks will look for deeper relationships with operational balances and an underlying mix of bank and treasury management services, as a backdrop for accepting non-operational deposits to reside on the bank’s balance sheet. Companies that have deposit-only banks for their excess cash may be steered towards off balance sheet products, such as money market funds or treasuries.

At the same time, corporates are gaining opportunities to access new solutions as banks innovate in response to the LCR: new products include notice accounts with maturities of over 30-days or ‘evergreen’ rolling tenors that reward clients according to the stability of their balances.

In anticipation of new products resulting from LCR, corporates will require a strong understanding of their daily cash positions. Strong cash flow management and enhanced forecasting can enable organisations to more accurately segregate operational and non-operational balances. Further segmentation into relevant liquidity buckets (daily operating, reserve and strategic) can help identify excess cash that can be committed for longer periods to alternative investment options and enhance yield. Corporates should work with their bank providers to find the right blend of products to match their mix of operational and excess cash.

Achieving visibility and control can enhance overall return on deposits whilst retaining access to their liquidity in the event of the unexpected.

Since 2008, companies have had a wide range of options for their excess cash including deposits as well as money market funds, commercial paper, government bonds and other fixed income investments. Given the costs associated with non-operational deposits, banks are more likely to steer excess cash to off-balance sheet investment solutions. It is important for treasury to review investment priorities in terms of security, liquidity and yield — reassessing corporates’ risk appetite - aligning its investment strategy and policy.

Additional cash efficiency may be achieved through centralisation and consolidation by using automated physical and notional liquidity management structures alongside multilateral and multicurrency netting, payment and receivable management and exposure and intercompany loan management.

Achieving visibility and control can enhance overall return on deposits whilst retaining access to their liquidity in the event of the unexpected. Although it makes sense for corporates to do this, up to now they have not been required to do so. However, in light of LCR, the effort required to enhance visibility and control of funds is justified.

As well as having direct implications for the types of products offered by banks, Basel III has other consequences for corporates’ investment policies. For example, the introduction of the LCR will provide a new way to assess the credit quality of banks. Corporates may start to use LCR figures, alongside credit default swap spreads, credit ratings, and other parameters, to gauge the strength and stability of their bank counterparties and their ability to remain liquid in the first 30 days of an idiosyncratic stress scenario. Consequently, Basel III may enable organisations to make more informed decisions about where they choose to invest their money.

In addition, the LCR could act as a ‘hallmark’, demonstrating that qualifying banks would be more stable in the event of a stress scenario. The ‘hallmark’ conferred by meeting LCR requirements could be an important new criterion when corporates select new bank counterparties.

The deposit rates paid to corporates by banks have always been affected by numerous factors, including banks’ business profile and domicile. Now, the LCR will add an additional element to this dynamic.

Although Basel III is a global regulation, implementation timetables, definitions, etc. are set either locally (in the case of the US) or regionally (for the EU). In the short term, this matters for corporates because the more gradual pace of implementation in the EU (see box for details) could affect the pricing that banks from different regions are able to offer.

Another implication of the regional implementation of Basel III is that the costs to banks of holding certain types of deposits – and therefore the pricing they can offer – may vary. Large US banks must comply with the proposed, and more stringent US LCR globally (plus local standards in certain cases), while some international banks may be held to less-stringent standards domestically and internationally.

Similarly, the proposed US LCR imposes different requirements depending on the size and type of organisation (see box for details), further varying the pricing that different types of banks are able to offer.

Companies must devise effective investment policies that reflect the broader potential market changes that could result from Basel III.[[[PAGE]]]

After 2008, diversification of risk became critical for companies, with the need to avoid over-concentration of banking products (including deposits) with any single bank. One unintended consequence of the LCR could be that corporates have less flexibility in where they place their excess deposits, unless they are willing to change the mix of operational and non-operational balances and transactional business they have with a bank. As a result, in order to continue to access more attractive products, corporates may end up with a greater concentration of their business with particular banks. However, it is important to note that companies may be able to diversify their cash using a range of other short-to-medium term off balance sheet investment options that may be available through a short-term investment portal.

If companies are not able to meet banks’ requirements in terms of their business mix, they may need to find an off-balance sheet home for excess deposits. This could lead organisations to consider a wider range of providers. It is essential that companies consider the costs, potential operational inefficiencies, and possible increased counterparty risk that could result from such a strategy.

Corporates will need to re-visit their investment policy, investment instrument mix and risk appetite (and commit to regular reviews in the future), in light of Basel III. They may also have to work closely with their banks to find appropriate solutions for their excess cash. Time is of the essence: markets conditions will change even before the launch of LCR in 2015 and investment policies usually require board approval, which can take time.

As well as focusing corporates’ attention on how to optimise their investment strategy, Basel III’s LCR should prompt companies to consider their overall relationship with banks. Companies’ cash management functions, such as payments and collections, which underlie deposits, will become more critical to banks given the value of operational deposits to banks’ LCR calculations. Corporates must ensure that their transaction banking relationships and investment policy are aligned, if they are to achieve their yield and security objectives.