After the Ballots

How the ‘year of elections’ reshaped treasury priorities

Published: November 04, 2013

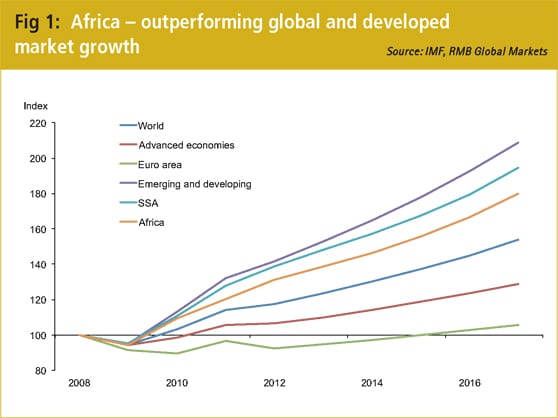

Interest in investing in Africa continues to grow, and although the story has been told many times over, it is always worth mentioning why Africa is an attractive investment environment for companies across the world. In RMB’s 2012/2013 edition of “Where to Invest in Africa”, it is noted that:

The operating environment in most African countries remains well below par, with access to financing topping the list in terms of the most problematic factors for doing business on the continent. The other factors making up the top five are: corruption, inadequate infrastructure, government bureaucracy and political instability. On the whole, Africa has struggled to improve its overall operating environment despite consistent growth in GDP and economic market size between 1995 and 2012.

Access to financing is particularly important when corporates look at how to fund their expansion strategies across Africa. While most African subsidiaries will generate profits in local currency, access to adequate domestic funding is often extremely problematic, from both a liquidity as well as a pricing perspective.[[[PAGE]]]

As a result, corporates are instead looking to raise hard currency funding as a means of financing their African operations. While the pricing is often much more competitive, it opens corporates up to significant currency risk due to the mismatch between their funding currency and their source of repayment (local currency income).

Therefore, the starting point in terms of a corporate treasurer making a funding decision in Africa is to fully understand this risk.

African currencies present unusual risks. In addition to the normal volatility risk, they may also have liquidity risk (being unable to deal because of a shortage of currency), exchange control risk (being unable to deal because of government regulations), jump risk (massive once-off currency movements) and/or trend risk (controlled steady movements in one direction). These risks are to a large extent determined by the currency regime in which they operate. In this environment proper risk management becomes more important.

The various currency regimes present across the continent can be seen in figure 4.

[[[PAGE]]]

Jump risk

This arises because many countries try but fail to maintain a set level of their currencies against a reserve currency (mostly the US dollar). This leads to periods of no or very low volatility, followed by sudden massive once-off movements as authorities give up on the old level. Typically, but not certainly always, these jumps are sharp devaluations, typically in the order of 10% – 30% and happen instantaneously or at most over a week or two. A clear example of such a move can be seen in the move exhibited by the Angolan Kwanza in late 2009.

Jump risk is more prevalent among managed/heavily managed currencies.

Trend risk

This arises as some African countries, notably Ghana and Mozambique, seem to prefer to spread out any currency adjustment over a period of time rather than do it all at once (jump risk). This generates small day-to-day movements (and so calculated low volatility) all in the same direction until a substantial adjustment has been achieved.

Liquidity risk

This is the threat of not being able to buy adequate hard currency in the local market. Ultimately this requires a devaluation of the local exchange rate to bring supply and demand back into equilibrium — which usually comes via a jump, as discussed above. Until the exchange rate is adjusted to a more competitive level, however, a shortage of currency would exist in the market.

Depending on the hedging requirement, we face different liquidity and product constraints in Africa. Funding also has liquidity constraints especially with variable regulations per country.

Available hedging instruments are specified in Table 1.

Hedging considerations

Although several African currency markets are fairly underdeveloped compared to American, European and Asian jurisdictions, there is still a significant amount that a corporate treasurers are able to do to mitigate their African currency exposure. In Zambia for example, capabilities exist to hedge up to a seven year USD loan via a USDZMW cross-currency swap. The cross currency swap in this case would effectively convert a USD loan repayment profile into an equivalent Zambian Kwacha one for the entire period, effectively removing all currency exposure for a Zambian subsidiary, which is using local currency to service its loan obligations.

The important next step for any corporate considering such a strategy is to compare the effective ZMW interest cost arising out of the swap, with which they could raise local currency on the ground in Zambia. While pricing would be the main consideration, one should also investigate whether or not the required volume of Kwacha is available in the market, as liquidity issues could significantly constrain the amount that can be raised in-country.[[[PAGE]]]

It is also worth mentioning that while a corporate can look to hedge their entire USD loan profile via a cross-currency swap, there may be several benefits to taking a more tactical approach to hedging. This could be done, for example, by hedging their quarterly loan repayments out to one year. Generally, African currency liquidity is much better for shorter tenors, often resulting in a significant pricing benefit relating to the forward cost of hedging.

Despite the very real impact that depressed commodity prices could have on overall African GDP growth, it is hard to dispute that Africa will remain one of the most attractive investment destinations over the next decade. With growing African credit risk appetite and ongoing financial product innovation in the sphere of corporate risk management, banks across the continent will hopefully be able to significantly deliver to corporates as they expand their African footprint.