After the Ballots

How the ‘year of elections’ reshaped treasury priorities

Published: July 01, 2013

As relationship business lending by banks continues to contract in many parts of the world, companies are looking for alternative financing tools. Particularly hard hit have been SMEs, even in rapid growth BRIC economies, who find it difficult to raise affordable credit. Larger corporations, sitting at the head of supply chains, while largely untouched by the credit squeeze, are concerned about volatility in their supply chains. They wish to avoid disruption resulting from financial difficulties amongst essential suppliers. As a result, recent years have witnessed a rise in the take-up of Supply Chain Finance (SCF) schemes, where larger corporations with access to more liquidity than they need seek to pass that benefit through to their smaller suppliers.

Demica has been tracking this market since 2010, researching emerging trends with the banking and corporate communities. This latest research report seeks broadly to scale current and predicted SCF market growth rates, the status of SCF alongside other trade finance products, along with opinion on obstacles and potential accelerant factors for this market to 2020.

Surveyed respondents have all experienced growth in their SCF business in recent years, with international banks in particular reporting significant growth rates. On a conservative estimate, annual growth rate of SCF averages between 30% and 40% in the last two years for global banks. One respondent from a multinational bank reported an increase in the number of their SCF programmes, along with an annual growth rate of 50% in the last three years.

A similarly positive growth trend has been confirmed by another commentator whose financial institution has registered a 35% annual increase in SCF assets in the last two and a half years. Another banking professional from a global bank even reported a 100% annual growth rate in the previous three years. Banks in continental Europe are also seeing a heightened level of supplier finance activities with one Dutch banker describing the growth of SCF at his bank in recent years as exponential. In comparison to 2012, his institution has already witnessed a 60% to 70% increase in the number of programmes in the first four months of 2013. His German peer from another major bank also confirmed a positive double digit growth rate.

The glut of activities in the SCF market is equally observed by multinational banks in Asia. According to one bank respondent from Asia Pacific, the growth of SCF has accelerated in recent years - a claim supported by the 300% year-on-year revenues growth of SCF over the past 12 months at his bank. He attributed this significant increase to the bank’s renewed focus on supplier financing and reprioritisation of its customer base. Another commentator from a Japanese bank predicted a double digit growth rate for at least the next four or five years.

Even though the majority of the respondents have witnessed burgeoning growth of SCF, it must be noted that this rapid advancement needs to be seen in conjunction with the relatively early stage of development of SCF as a widespread and standard banking product. In some markets, SCF has just started to take root, as highlighted by a Swedish banker who said significant growth has only begun to take place in his domestic market over the last couple of years. Encouraged by the swelling ranks of institutions offering supplier financing to corporate customers, one Irish banker noted his bank has only recently made a foray into the SCF market. In Africa, SCF is still in its infancy, noted a financier in the region. According to him, a few international banks are marketing SCF in South Africa, but their scope of activities is rather limited, which is why his bank is currently developing the product for the African market.

Even though virtually all interviewed respondents whose banks are active in the SCF arena have seen growth, the magnitude of growth experienced by our qualitative sample of domestically focused banks is much lower. One commentator from a regional German bank indicated a growth of close to 5% in recent years. Another financier from a regional bank active in North America reported a tremendous increase in demand for SCF solutions after the credit crunch. However, as the bank could not grow as fast as the rising demand, its overall growth rate was only around 6%.

According to respondent opinion, growth of SCF is the most prominent in the US, followed by Europe, in particular the UK and Germany. Other European countries highlighted include Italy, France, the Netherlands, Ireland and Denmark. An increased level of activities in central Europe including Poland, the Czech Republic and Croatia is also reported, with Eastern Europe considered to have huge growth potential.

In Asia, strong growth momentum is witnessed in India and China, but also Malaysia and the Philippines. Highest growth of SCF in industry sectors is said to originate from retail, manufacturing (especially heavy industry), consumer goods, automotive, agriculture as well as chemicals and pharmaceuticals. The energy sector, as observed by one respondent, is also beginning to make increasing use of SCF.[[[PAGE]]]

Respondents were all positive about SCF growth in the near future. Banks that have just ventured into the market are experiencing a flush of early success in the field. On the other hand, some international banking behemoths have also witnessed tremendous growth of SCF in their businesses in recent years. Collectively, there seems to be a shared sense that the rate of growth will moderate as such momentum will not be sustainable in the long run. Nevertheless, a conservative estimate on the future annual growth rate of SCF by 2015 still averages between 20% and 30% based on the aggregated findings. By 2020 average yearly growth rate is still estimated to be more than 10%. One commentator who expected the market size to double again by 2015 remarked that because of the way the product is structured, there is a finite limit on the number of businesses SCF can be offered to. She believed that at some point banks will have to give thought to the design of the product going forward in order to meet a wider spectrum of business needs, and avoid the commoditisation that comes with market saturation. Another financier suggested that in the long run, the SCF model may change as an increasing number of companies explore self- funding. He opined that up to now, companies have been looking for a bank to administer and take charge of the entire SCF programme, but looking ahead, businesses may think of using future cash reserves to put SCF programmes in place. He confirmed that the bank-administered growth rate will continue well into 2020, albeit with a less aggressive pace.

Owing to the emerging need to cater for companies of different sizes, one respondent believed the market will see more secured types of products that might not even necessarily be off-balance sheet. Another US financier predicted a continuing rise in the number of SCF providers in the market space. She reckoned that in the past, SCF was normally offered by a banking institution which also provided a suite of other products and services to its clients. That scenario is changing with the growing number of non- traditional players such as hedge funds buying into SCF assets.

Aggregating the views of the respondents, the main drivers for SCF are considered to be: 1) the provision of liquidity to suppliers; 2) working capital optimisation and 3) enabling payment discounts/cheaper financing costs for suppliers. Risk mitigation in the supply chain is also regarded as an important driver, though as one respondent pointed out, a meaningful SCF programme for risk minimisation should include at least 30 - 40% of the supplier community. A handful of respondents also mentioned that the more pronounced sense of corporate social responsibility (CSR) has contributed to the growth of SCF as buyers are trying to ensure that their desire to extend payment terms does not translate into additional financial strain for the suppliers. With credit agencies scrutinising the cash positions of companies and publishing peer group analysis, as highlighted by one commentator, firms that can show effective management of their own working capital and that of their supply chain are distinguished from competitors that cannot demonstrate this capability.[[[PAGE]]]

According to one financier, many suppliers really appreciate the strategic support provided by a buyer who offers an SCF programme. Another respondent also believed that this alliance increases the attractiveness of supplying to one particular company. A number of banking professionals made the observation that many buyer companies can command considerably more liquidity than they need for themselves, and are therefore looking to pass on the benefit of that available working capital to their supply chains, which often have difficulty raising affordable finance.

Most respondents were also of the view that technology will play an increasingly significant role in facilitating the development of SCF as it can determine the breadth and depth of a SCF offering. This is particularly true as businesses nowadays not only focus on working capital benefits, but also operational efficiencies and cost reduction, as these bankers suggested. The combination of SCF and e-invoicing in particular is seen to be a huge step that can greatly improve process efficiency. One financier highlighted the fact that with e-invoicing, the transfer of invoices can be accelerated, thus allowing banks to provide faster financing. Nevertheless, he noted that there is still little connectivity between the providers of SCF and e-invoicing technology vendors at this stage.

Interestingly though, one banker added that the main technology challenge is not so much related to the newer e-invoicing developments, but more a matter of legacy systems integration. In his opinion, ERP integration with the receivable and payable parties is the key for securing seamless and straight forward processing as well as maximum connectivity. The connectivity between a SCF platform and the back office, as emphasised by another respondent, is imperative for the creation of a fully automated solution. This opinion is reflected in another financier’s comment that clients are looking to gain internal efficiencies in their payment processes through efficient linkage between their ERP system and the bank’s platform. In connection to this, one financier also remarked that many companies are taking a very serious look at their ERP systems as the room to automate the physical supply chain has more or less been exploited, therefore the focus has now shifted to achieving maximum financial efficiency in the supply chain.

Some commentators also believed that increased visibility for suppliers is an important technological driver for SCF. Normally when suppliers send out an invoice, they can never be certain if it will actually be paid on time. However, within a SCF programme, suppliers can have visibility of invoice approval and payment process, giving them confidence about the timing of invoice settlement, allowing them to better manage their cash flow. One banker also opined that some companies are hesitant to provide SCF because of the associated processing costs. Therefore, if technology can help drive down the cost of the initial investment, SCF should experience greater take-up.

A number of respondents also felt that there is real demand for more sophisticated SCF solutions. One believed that such programmes are necessary because SCF can be viewed from various strategic angles. Buyer corporates, for example, might be interested in a multi-bank programme where they would have the need to operate on a consistent platform. Moreover, a couple of financiers also said they are beginning to see large corporates contemplating the set-up of a SCF programme using their own funds. In these cases, the corporates are looking at technology and financial structures which are optimal for their balance sheets as well as allow them to make good use of their excess cash or release trapped capital. For example, they might want to leverage their excess cash positions in jurisdictions where there is trapped cash – such as China, Indonesia or India.

Almost 90% of the respondents regarded SCF as a need-to-have for corporate buyers as opposed to a nice-to-have, with more than 75% of them considering it an added-value product. However, with the increasing utilisation of SCF, approximately 80% of financiers interviewed believe that SCF solutions will commoditise somewhat by the second half of the decade. Increasing market demand for SCF is also likely to lead to emergence of new players and therefore fiercer market competition.

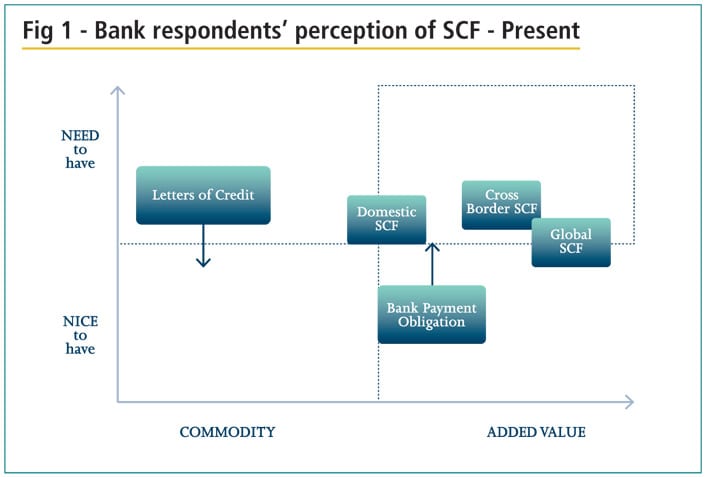

In order to give a more detailed perspective on SCF, bank respondents were also asked to differentiate the current market position of domestic, cross-border regional and global SCF programmes against the parameters: need to have/nice to have and commodity/added-value. A similar exercise was conducted with corporate respondents – a qualitative sample of international companies. The aggregated findings are illustrated in figures 1 and 2. It is clear from the illustrations that both banks and corporates share a very similar perception of the three SCF models, with banks slightly more inclined to see SCF as a necessary product for corporates. However, it is apparent that both parties consider SCF as a value-added product at this stage.

Bank respondents were also asked to predict the future market position of the three SCF models, as shown in figure 3. Corporate respondents did not feel sufficiently qualified to make firm future predictions. However, given that their current view on SCF is closely aligned with the banks’ perception, one might assume that their future view on the product will mirror the bankers’ predictions.

One commentator who focuses on the central European market opined that SCF is an essential tool in managing working capital for his clients. In his view, there has been a gradual change in attitude amongst banks and they are now increasingly targeting medium-sized corporations. Another banking professional was of the opinion that in addition to achieving financial efficiency, peer pressure can trigger a snowball effect and make implementation of SCF an imperative. In his observation, when one company starts focusing on receivables and payables, other businesses will feel pressurised to examine the subject so that their cash management does not appear out of line with their peers.[[[PAGE]]]

A number of respondents felt that SCF is not just an essential facility for banks’ corporate clients, but indeed also a need-to-have offering for banks. With increasingly stringent financial regulations, one financier believed that SCF will become even more of a need-to-have for large banks as straightforward balance sheet lending will become more costly. The comments of another commentator were typical of respondents, when he observed that his bank has made SCF a core pillar of its Trade Finance group owing to the climbing demand for supplier financing from clients, which consists of mainly blue chip companies and medium-sized enterprises. This respondent predicted that the financing of working capital will become more closely linked to the actual flow of goods, receivables and payables. Bank financing for inventory, for example, will become more aligned with information from the actual inventory flow so that financing adjustments can be made accurately and swiftly. He attributed this trend to the increasingly sophisticated ERP and e-invoicing systems, making relevant information on the flow of goods more readily available for banks.

This financier also noted that SCF is still very much an added-value product at the moment as there are still many differentiations among banks on their SCF offerings in terms of jurisdictions, automation levels, reporting, platforms, etc. Nevertheless, as corporates are showing heightened interest in SCF, one commentator expected greater focus and efforts from the banking community to drive SCF towards standardisation and lower pricing. Another banker added that SCF currently still resembles more of an ancillary product instead of a core banking facility, but she believed it would become more widely recognised as a stand-alone service by 2015.

Once SCF becomes more commoditised, attention will focus on price competition between banks, suggested one UK respondent. He predicted that banks will have to work in collaboration because of the increasing size of the schemes demanded by the market and this will lead to a harmonisation of pricing. Clearly, the majority of the bankers shared the view that it will take time before SCF has established itself as a thoroughly mainstream product, but one US banker maintained that available technology is already accelerating that process. In her opinion, an increasing number of platform providers for supplier financing programmes have helped reduce required initial investment into systems and resources, hence minimising barriers to market entry for smaller banks.

When asked to describe the relationship between SCF and other trade finance products, over 80% of the respondents considered it complementary. If there is only limited trading history between buyer and supplier, letters of credit might be a preferred option. However, if there is a deeper relationship and the purchase volume is significant, SCF is considered more desirable since it reduces the administrative burden. According to one financier, given the gradual decline of traditional credit instruments such as letters of credit, now further accelerated through the introduction of Bank Payment Obligation (BPO), corporates are becoming much more active with open account solutions, making SCF a good complementary product. Another respondent remarked that SCF will make a good complement to e-invoicing as this technology by itself is not yet a revenue generating product.

Only a small percentage of the respondents believed that SCF might displace other means of receivables financing, specifically factoring. As pointed out by one banking professional, if suppliers are discounting their invoices under an existing factoring arrangement, they will have to leave those arrangements in order to join a SCF programme. Sometimes, this respondent’s bank will move those suppliers from the bank’s own factoring agreement onto an SCF arrangement at the suppliers’ request. A few respondents felt that SCF might gradually replace a proportion of straightforward balance-sheet lending. Another financier was convinced that even when SCF becomes more widely adopted, it will only reduce the extent to which other core banking facilities are used but it will never fully replace them.

At the moment, only 20% of the surveyed banks promote SCF equally as a stand-alone and an add-on product. 60% of the banks promote SCF only as an add-on offer, compared to 20% of those promoting it principally as a stand-alone service. Around 35% of the respondents’ banks provide SCF to their existing customers only, with the rest willing to extend this credit facility to both existing and new customers (dependent on credit status). One financier noted that an existing bank relationship is a pre-requisite for the service since her bank is only aiming to provide SCF to companies with whom they can develop a deeper relationship. This is echoed by another respondent whose bank’s strategy is to increase customer penetration through the provision of holistic solutions. Given the current regulatory environment, his bank is more focused on retaining existing customers than capturing new prospects. Another banking professional added that his bank does not market SCF on its own as they see it as one part of the suite of solutions they offer for working capital optimisation. This mentality is shared by another Swiss commentator who considered SCF a service positioned between open account cash management and letters of credit.

For those whose banks are less restrictive with the choice of potential clients, they believed that SCF can act as a door opener to further business opportunities. One banker noted that some of their clients are only interested in the financing aspect of SCF, while the others might want to exploit the efficiencies in managing payables in combination with other products, thus his bank is prepared to provide SCF as a stand- alone or add-on offering. Nevertheless, his institution only offers SCF to corporate institutional clients with a minimum turnover of 100 million Australian dollars.

Just over one-third of the respondent banks are mainly focused on domestic SCF, with another quarter active in both domestic and cross-border regional financing programmes and a further generous third also engaging in global SCF programmes. A few banking institutions maintained that they do not harbour any ambition to extend their domestic programmes to cover a wider spread of countries, but these do tend to be regional banks. One financier asserted that the largest part of his clients’ supply chain is actually domestic, especially in some of the larger GDP countries where the buyers are located, such as the UK, the US, France and Germany. His bank is therefore seeing an increasing number of clients looking for solutions that have a local or regional focus rather than global. This view is also reflected by another respondent’s comment whose bank offers both domestic and regional programmes. His bank is now re-prioritising the domestic market, which they previously underestimated, with increased efforts and they are seeing an encouraging business pipeline.[[[PAGE]]]

Others are having a different experience. One respondent whose bank’s engagement in SCF is equally split between domestic and international programmes is seeing a higher growth potential on the global side. Another financier whose bank has a 40%/40%/20% focus on domestic, regional and global programmes respectively is also anticipating more global deals in the future. He noted that at the moment many banks are focusing on domestic growth due to political and regulatory pressure to finance locally, especially those that have shareholders with government ties. One commentator added that since global programmes usually offer the greatest interest rate arbitrage between buyers and suppliers, there is more value to be extracted than a domestic programme. However, according to one respondent, there are not so many truly global programmes from the buyers’ perspective. Many companies have neither centralised their procurement nor developed a homogenous IT system; it is therefore very complex to set up a single global programme for all their supplier firms.

In comparison to a domestic SCF programme, there are inevitably more challenges and complexity associated with the setting up of a cross-border offering. Local regulations, multi-regime compliance and on-boarding suppliers are regarded by the respondents as the three most challenging issues. Banks need to have a thorough understanding of the local legal framework in order to ensure that legal structures are enforceable and applicable. They also have to examine all supplier and buyer jurisdictions covered in the programme and scrutinise the tax position and documentation proposition as well as understand the local trade environment. As one banker explained, this high level of data compilation is a considerable investment cost, which is partly the reason why there are only a few global banks that have the ability to offer international SCF programmes thanks to their reach and global support model.

Where banks do not have a local presence, the execution of Anti Money Laundering (AML) and Know Your Customer (KYC) checks becomes even more challenging. One respondent therefore believed that the implementation of KYC through local and international alliances is essential for the SCF market. Of course, there is also more complexity on the buyers’ side in a multinational SCF programme as more decision makers will be involved, as one banker highlighted. He noted that this area of complexity will remain unless customers centralise their decision making processes. Apart from the legal perspective, one commentator added that cross-border programmes also present a challenge from a system (e.g., languages, currencies etc.) and an accounting perspective, though he believed the value can be maximised to a greater extent in a cross-border offering than a local one.

Regardless of the geographical scope of the programme, on-boarding suppliers can be a challenge. To facilitate this process, financiers emphasised that it is fundamental to help suppliers understand the proposition. It is also critical that banks can provide a high level of support to those who need to secure approval from the senior management at the buyers’ companies. One respondent actually believed that supplier on-boarding has slowed down potential growth in SCF. Since SCF is being promoted by the more developed parts of the world, he pointed out that the expertise still resides in those regions. So even if a bank has a local presence, that expertise is not necessarily transferred to the local subsidiary and the SCF concept might not be explained and expressed properly. As increasing uptake of SCF really depends on skilled marketing teams being able to explain the proposition to suppliers in an effective and clear way, he believes that it takes time to develop an educated supplier base.

The majority of the financiers surveyed believe that generally speaking, buyers have a fairly good understanding about the working of SCF and its interest rate arbitrage. According to one commentator, SCF is a known product in the US, but he also observed that it is becoming more of a standard within the treasury and finance community in Europe and in Asia. T aking Germany as an example, he asserted that the awareness of SCF was very limited four or five years ago, but German companies that are active in international trade are now very much familiar with this product. In his opinion, the education level of SCF has risen dramatically over the last couple of years since many companies have been looking for alternative sources of finance due to the squeeze on balance sheet lending to supplier communities, and the resulting threat of instability in the supply chain.

One UK banker noted that the treasury teams that he has dealt with usually do have a very good grasp of SCF, but whether this superior understanding can be cascaded down to the procurement teams that have to interface with the suppliers is often another matter. This view is echoed by another banking professional who remarked that the practicalities of implementing the programme can still prove challenging internally despite good knowledge of the product. In order to ensure an efficient execution of the programme, as she explained, different stakeholders in the organisations have to learn to view things in a different way and that requires a great deal of project management and education.

One US respondent said that her bank is investing a great deal of time and resources in helping middle market companies understand the product. An Australian banker noted that in-depth awareness is still missing at the moment and he proposed that part of the selling process should focus on educating the CFOs and treasurers on the buyers’ side about the possibilities, causes and effects of these types of supplier financing arrangements. A few financiers, in particular those who are based in emerging markets, still found buyers’ understanding of SCF rather insufficient.

Looking at the suppliers’ side, there is a consensus that understanding is still immature. This of course might not be the case for large suppliers, but it certainly holds true for the majority of SMEs. A number of respondents raised the point that sometimes suppliers might harbour a sense of cynicism or scepticism about tying themselves to their buyers. They might also assume that there is a hidden agenda because the offering just seems “too good to be true”. As these financiers pointed out, it is therefore important to help small-end suppliers understand the cost of their current working capital and the interest rate arbitrage they can leverage using the credit rating of a large business. One respondent added that banks have an essential role to play in educating the procurement arm of the buyers so that they can explain the subject matter confidently to their suppliers. His bank, for example, provides suppliers with educational packs in order to describe the SCF concept, its advantages as well as the goals and strategy of the buyer.[[[PAGE]]]

In the opinion of financiers interviewed in this survey, only the British government is seen as actively advocating SCF. British respondents all very much welcome the official SCF initiative, with one of them saying that the level of government support in this area is pioneering. Another commentator remarked that the UK government is now realising that the economic recovery will have to be driven by SMEs and it is therefore of utmost importance to ensure that they are in a cash neutral or cash positive position. One US financier commented that during the financial crisis, the US government also created an SCF product that was catered specifically to the suppliers of automotive parts. But with liquidity returning to the market, the respondent believed that the authorities are no longer putting as much emphasis on the programme as they did previously.

On the topic of financial regulations, the majority of the respondents believed that there will not be any major impact on the SCF market. Several banking professionals were actually of the opinion that some of the regulations might have a positive effect on SCF. One of them noted that Basel III might make SCF a more attractive product for banks, as the early indication is that SCF assets will be considered as trade paper and thus there is no requirement for banks to hold capital for them, leading to potential price advantages to the users. Another banker held a similar belief that as debt is more expensive under Basel III, the fact that SCF is not regarded as debt for suppliers will give it a competitive edge. This view is also shared by another commentator who observed that businesses are moving from other banking offerings to SCF as some of the other products are receiving an adverse impact from regulatory changes. In his opinion, regulators have not done enough in recognising trade as the engine of economy and the role of SCF in enhancing trade.

Regarding the European Payment Directive, almost all of the respondents said that they have not seen any impact on the SCF market. As there is clearly room for a range of interpretation as the Directive is not enacted into local statute and statutory instruments, a number of financiers questioned its real impact. The general consensus is that any effect would be rather limited unless a law emerges that actually makes late payment a criminal offence. One financier remarked that in France, where payment terms cannot legally exceed 60 days, businesses are rather nervous about introducing SCF as they struggle to see the benefit of such programmes when they are already adhering to the law.

The banking community has clearly stated that greater understanding and appreciation of SCF among corporates is critical to maintaining growth in the market. In order to take the pulse of the corporate community, this qualitative research study interviewed a selection of multinational enterprises.

Many of the respondent corporates have only recently embarked on SCF programmes, providing representation from the current cohort of SCF users, rather than the handful of pioneering corporates in the field. The most common driver behind an SCF initiative is working capital optimisation. According to one automotive company, the initial motive was to leverage their balance sheet and reduce costs within the whole supply chain. They expected their programme to grow by a further 20% by 2015.The key driver for an international beverage company was the need to maintain its credit rating after a considerable rise in debt level following an acquisition. At that time, the company was examining different focus-points of cash generation within the business in the hope of achieving one of the following: improved financial transparency; delaying payment; or speeding up cash conversion. The company is now expecting significant growth of its SCF programme in the next few years. Another company - this time in telecoms - noted that improving the flow of working capital was the main motivation. It believed the growth rate of its programme will triple by 2015.

Asked whether their SCF programmes are well received by the supplier community, several respondents believed that the acceptance level is different for each operating country depending on available liquidity in the local market. One commentator from a consumer group company highlighted that their local SCF programme in Spain has already been running successfully for a long time. He noted that such programmes are very common in Spain and the local banks there all have a very good infrastructure to support the suppliers. At the moment, his company is working on an SCF programme in the Netherlands and its goal is to on-board as many suppliers as possible as they are very keen to offer their suppliers a mechanism to obtain cash early. However, he has the impression that banks tend to “exhibit interest in high-end numbers only”. As small companies are having difficulty accessing finance, he believed that corporates have the social responsibility to ensure that their smaller suppliers do not suffer from buyers’ desire to extend payment terms. SCF will help to serve this purpose but he suggested that banks first need to “change their fixation on big figures”. Through SCF his company has been able to shorten the payment periods from 50 - 55 days to 15 days. Most of the smaller suppliers in his supply chain are able to benefit from the lower interest rate they pay for the programme than their marginal cost of funding.

In comparison, two other commentators remarked on a more selective approach of their companies when offering the product to suppliers. One of them noted that they want to keep the programme at a certain size, so they have not offered it to the whole supplier base as it would be very time consuming for finance staff. Nevertheless, the facility was well received and the company has managed to improve terms. Another respondent from a telecommunications company also reported that supplier financing has helped it increase scope of business and improve relationships with suppliers.

Regarding suppliers’ understanding of interest rate arbitrage, the general impression indicates that there is still a knowledge gap to be filled. One respondent recalled that in his experience, suppliers are often pleasantly surprised about the interest rate. To make SCF a successful programme, he stressed, it should be a win-win scenario for both buyers and suppliers and buyer corporates should not keep all the advantages for themselves. This sharing of benefit is really important, as emphasised by two other corporate commentators, and it needs to be properly explained to suppliers in order to overcome that initial scepticism and to help them understand the virtues such as cheaper financing cost and preservation of credit lines with their relationship banks.

Respondents also believed that there is demand for more sophisticated SCF solutions, especially for global programmes or centralised organisations and they agreed that technology will be an important enabler. E-invoicing, in particular, was highlighted by a number of respondents. Its ability to accelerate the invoice approval process and to ensure correct data right from the start is particularly appreciated. Another commentator added that the increased visibility and transparency is something that is very valuable for their suppliers.

On the topics of challenges in implementation, there are different opinions. One respondent believed that the major challenge is to make the scheme attractive to suppliers. In his view, the financial benefit needs to be evident and be demonstrated to the suppliers. In some countries where suppliers have good access to financing, it might prove more challenging because the financing argument is missing. Nevertheless, there are operational efficiency gains to be made – a message that needs to be communicated across the supply chain. This view is reflected in another respondent’s comment, where they noted that it might take more effort to convince larger suppliers to participate in the programme, but on-boarding smaller suppliers, in his experience, is usually quite easy.[[[PAGE]]]

A corporate treasurer raised the issue of gaining internal support. He noted that the process can be rather long-winded as companies need to garner support from the management and then promote the idea to the purchasing team and train their buyers before approaching suppliers, where the persuading continues and potential savings need to be explained. Regulation was cited by one respondent as the most challenging matter, but at the same time, it has been a driver for his company. He explained that the local law in Columbia had been amended so that invoices were assumed approved after 14 days, if not rejected by that point. Yet his company’s systems at that time were not able to approve the invoices within such a short timeframe. Despite this, suppliers were able to factor their outstanding invoices after the 14 day period, causing confusion over to whom the debt was to be paid, and raising the possibility of unapproved invoice debt being sold to third parties. His company therefore embarked on a supplier financing solution in Columbia which they are now also planning to roll out into Peru, where the same law will also take effect.

Finally, corporate respondents shared a rather positive view of banks’ efforts to promote SCF, believing that banks are putting sufficient efforts and resources to promote the offering. According to one commentator, banks are already doing a good job in the US, European, Australian and even Asian banks are also becoming more active, but banks based in Latin America and Africa are lagging behind. His opinion is shared by another respondent who noted that SCF expertise and experience is lacking in markets such as Latin America or China, where a large proportion of suppliers are located. That is a situation that needs to be changed as he predicted a shift in the momentum of SCF towards these markets in the future.

Bankers and their corporate customers appeared to be broadly aligned in their view of SCF and its development – in other words, a relatively young market experiencing rapid growth, which will slow over the rest of the decade as demand fuels competition and bank offering becomes more standardised and commoditised. Cross-border SCF programmes were expected to grow strongly, but retain value-added status by virtue of the greater complexity than their domestic equivalent. Tightening banking regulation was seen as far less an obstacle than having to deal with multi-currency, multi- legislation complexities.

Interestingly, supplier on-boarding, formerly cited as a major obstacle to SCF growth, was revealed largely as a matter of education and communication of scheme benefits to the supplier community. Corporates firmly indicated that banks need to create effective support packages to get the message across to suppliers.

A minority of bankers were promoting SCF as a stand-alone service, but most regarded it as an increasingly important pillar in their trade finance offering. Finally, from a technological point of view, growth in the e-invoicing market was seen as likely to provide a significant boost to SCF growth.

Research was conducted amongst a global sample of banks during April 2013. Specifically, the research was conducted amongst the European top 25 banks, plus a qualitative sample of international banks from Asia, Africa and the United States. Furthermore, the same questions were also presented to 14 international corporations to gather qualitative validation of the trends identified by international banks. The selected sample of international corporates ranged across a spectrum of industries including telecoms, automotive, information, retail, manufacturing, construction and consumer goods. Global bank respondents were asked about their views on the growth of SCF, their perception of this financing facility as well as their banks’ approach to this offering. Corporate respondents were interviewed on their usage of SCF, main drivers for introduction, experience with the programmes and implementation difficulties.