After the Ballots

How the ‘year of elections’ reshaped treasury priorities

Published: November 04, 2013

Companies operating in South Africa consider rand volatility to be a major problem. Ninety-one per cent of respondents to our currency risk management survey rated their companies as being sensitive or very sensitive to the exchange rate. The less systematic the company’s hedging practices, the more likely it was to be highly sensitive to exchange rate moves. Encouragingly, the survey suggests that a sound framework for currency risk management is well entrenched and that hedging instruments are well understood. However, these findings are less conclusive for small and medium-sized firms, which were more likely to have a less systematic approach to currency risk and less likely to be comfortable with hedging instruments and strategies. Views were mixed on whether regulatory issues (exchange controls and hedge accounting) complicate exchange rate risk management.

In July 2013, National Treasury and Rand Merchant Bank (RMB) surveyed companies operating in South Africa in an attempt to better understand their currency risk and currency risk management operations. We extend our thanks to the ACTSA members who participated. The 192 respondents were largely involved in currency decision-making and operated in a range of sectors, with particularly heavy representation from the manufacturing sector and larger businesses. This article summarises the survey’s results.

The currency is a major concern for South African businesses, with 67% identifying it as one of the top three risks facing businesses. Cash flow (43%), commodity prices (41%) and political risks (36%) were the next most frequently raised issues.

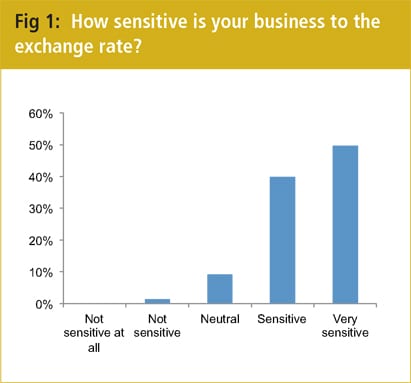

Businesses appear highly sensitive to the exchange rate. Fifty per cent of participants said their businesses were very sensitive to the exchange rate and another 40% said they were sensitive (Figure 1). This is similar to the responses to a survey conducted by RMB in 2010 (RMB 2010 survey). The high sensitivity to the exchange rate came from all industries, across all sizes of companies, and covered exporters, importers and those with relatively limited trade.

Respondents indicated that the main reason for this sensitivity was a high dependence on imports and/or exports (Figure 2). This held even if they classified themselves as having exports and/or imports at lower than 20% of revenue/costs. The second most commonly expressed reason for the high sensitivity was that companies aren’t able to pass currency moves on to customers.

A high 32% of companies believed that currency fluctuations create balance sheet risks. This refers to ‘translation’ risk: under accounting guidelines, foreign operations need to be consolidated into the balance sheet at the exchange rate at the end of the period. As the exchange rate adjusts, so does the consolidated value. Under the Active Currency Management (ACM) exchange control reform implemented in 2010, it is now permissible to hedge this risk. However, while RMB has carried out these translation hedges, this market is still in its infancy in South Africa.

The business impact of a volatile currency seems greater in inhibiting investment than trade. Seventy-seven per cent of respondents felt that currency volatility impacts their long-term investment decisions. This shows that the rand’s extremely high volatility – it competes with the Brazilian real to be the most volatile in the world – has a real negative economic consequence.

By contrast, only 12% of those companies where exports account for less than 20% of revenue gave currency fluctuations as a reason for not exporting more, with more than 50% noting that exports are not part of their business strategy. Around 40% of manufacturing firms raised issues around competitiveness and about half that number raised issues around currency fluctuations when explaining the relatively low share of exports in their revenues. Other export constraints mentioned included high labour costs, unfavourable freight costs and the inability to compete with China and other low-cost producers. Encouragingly, a frequently repeated answer was that exports are a growth area, even though currently only a small part of the business.

Of those companies where imports account for less than 20% of costs, 55% choose not to import more because they find that all their needs can be satisfied locally, with only 17% finding that currency fluctuations inhibit greater imports.[[[PAGE]]]

Participants believe that their companies generally adhere to good principles of hedging practices. Asked what best describes their company’s approach to managing exchange rate risk, 63% stated they take a systematic approach by either eliminating all the risk they can by hedging or transacting at spot (Figure 3). A further 32% selectively hedge. No respondents admitted to speculating, which is illegal, and only 14% said that they try to time the market. These results suggest a significant shift from the RMB 2010 survey, when only 35% of respondents took a systematic approach to hedging and more than 30% tried to time the market.

Corporate frameworks seem largely supportive of good hedging practices. Sixty-four per cent of respondents believe that their management understands the value of hedging. Two-thirds of businesses feel that they have a systematic rather than ad hoc approach to managing risk, and 75% believe their company evaluates the currency risks it faces regularly. However, a sizeable 34% also agreed or strongly agreed that the treasurer has to act on judgment rather than protocol when deciding when to hedge.

Participants were confident in their ability to understand complex areas relating to hedging. Only one in five respondents find that hedging instruments are hard to understand/seem risky and few find it difficult to construct a portfolio of rolling hedges (Figure 4). Remarkably, not many respondents said they find it difficult to estimate currency exposure (Figure 5). This contrasts strongly with international surveys where this area is shown to be the most difficult aspect of currency risk management.

The difference between the local and international experience could be due to size: large multinationals could find it more difficult to estimate currency exposure than local companies. It could also be due to a historical legacy from exchange controls. Pre-ACM, companies needed a firm and ascertainable commitment before hedging and, although this has been abolished, business processes and thinking have perhaps not adjusted.[[[PAGE]]]

Most treasurers found regulatory factors difficult. Only around 20% of respondents agree or strongly agree that the cost of hedging makes currency risk management unviable. By contrast, around 50% agree that accounting issues complicate currency risk management, and 45% found that complying with exchange controls complicated hedging (Figure 6). Comparing the current results with the RMB 2010 survey, it appears that accounting issues are now more problematic, whereas exchange control issues have become less so.

There is, however, significant variation in treasury management by business size. Larger firms are generally more sophisticated, as could be expected given their resources to develop specialised treasury functions. They are more likely to believe that hedging instruments are easy to understand and their treasurers are much less likely to have to rely on judgement rather than protocol in currency hedging. Interestingly, however, these same firms are more likely to admit that accounting for hedges complicates hedging than smaller firms. This may be because of a deeper understanding of the complexities involved.

By contrast, smaller businesses in the sample, with turnover of less than R250m a year, say they try to time the market more and have less understanding of hedge instruments. They are much less likely to disagree that the company has an ad hoc approach to managing currency risk, that treasurers act on judgement, or that the cost of hedging is an obstacle to business. Those with turnovers of less than R14m a year find that currency exposures are hard to estimate and tend not to have a system of evaluating currency exposure on a regular basis.

There are also important differences between corporate treasurers and other business respondents. Those who are not involved with the day-to-day operations of the company are more likely to say the currency is a significant risk (80% versus 67%) and are also more likely to say this is because of export or import dependency. Non-treasurers are also more likely to believe that the company has an ad hoc approach to currency risk, that estimating currency exposure and using hedging instruments is difficult and that exchange controls pose an obstacle to hedging. They are, however, less likely to believe treasurers act on judgement and are no less likely to agree or disagree that rolling hedges or accounting for hedges is difficult.

Encouragingly, the survey suggests that a sound framework for currency risk management is well entrenched and that hedging instruments are well understood. However, the generally high levels of sophistication displayed in the survey belie apparent knowledge gaps. Smaller firms’ treasury frameworks seem relatively underdeveloped while medium sized firms may need to be sensitised to more sophisticated issues such as constructing rolling portfolio hedges and hedge accounting. It was striking that larger firms were more likely to agree on the difficulties posed by hedge accounting and smaller firms were less likely to find constructing rolling portfolio hedges difficult, which could reflect the greater use of and exposure to more complicated hedging strategies of the larger firms.

The relative importance of hedge accounting in complicating risk management for medium and larger firms is worrying since accounting should, of course, be auxiliary to the economic decision of risk management. Unfortunately in South Africa, as is the case worldwide, accounting issues can affect real decision-making. This is an issue that the accounting authorities are trying to deal with.

The slight improvement in the perceptions of exchange control issues since the RMB 2010 survey is somewhat comforting, but still of concern. ACM means that there are now in fact very few restrictions of what and how currency risks can be hedged away — implying that the benefits of ACM have not been fully utilised by the private sector. This is certainly RMB’s view, which finds that even three years after exchange control relaxation, many corporates are still wedded to the historic process of only hedging if and when there is a firm and ascertainable commitment. A better understanding of what is feasible under the current exchange control regime should reduce the number that believe that exchange control is an obstacle – participants that are directly involved in the currency operations of the business are less likely to view exchange controls as a problem than those who have no direct involvement.

This survey provides a useful platform for discussions around treasury management. Should you wish to discuss the results in more detail, do not hesitate to contact Catherine MacLeod or John Cairns directly.