After the Ballots

How the ‘year of elections’ reshaped treasury priorities

Published: October 01, 2010

This article discusses key strategic thoughts behind deciding when and how to hedge. It addresses the main pitfalls, inherent and new challenges as well as the education of the board and essential internal hedging reporting. It also defines the appropriate tools to face (new) accounting issues, with IAS 39 and its ‘son’ coming soon. Eventually, the OTC derivatives reform and its potential impacts on hedging strategies had to be further explained.

If we refer to the comments of Merton Miller, winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1990 for his pioneering work in the theory of financial economics, we might conclude that hedging serves no purpose: “The most value-maximising firms do not hedge”. But can we as treasurers accept this statement at face value? Wouldn’t that amount to the negation of our profession? Even if we take into account the context of his words, and even if we accept that hedging means taking a decision and making a choice that could lead to a possible loss of opportunity, it strikes us as inadvisable to adhere purely and simply to Merton Miller’s theory (with due respect to the man and his work), as well as to his colleague Franco Modigliani.The academic issue here is whether hedging ‘creates value’. In certain cases, hedging is an obligation (contractual in the context of credits) and, in imperfect markets, sometimes makes it possible to continue to borrow. Hedging also enables treasurers to concentrate on the operational and management sides, and can create value when it sustains the company’s activity and ensures the continuity of its main aim and corporate purpose.

Non-financial companies don’t at all like speculating and remaining completely unhedged. Imagine the totality of exposure to one or more risks, such as all of the exposure to the USD, and apply to it a stress-testing factor of 20%, for example. While the CFO could live with such an impact (even if, in part, the accounting P&L result would not be affected by off-balance sheet underlying commitments), there is a high likelihood that it would not accept or tolerate such an impact, even a potential one. Just think of the amount recorded in OCI/EHR (Equity Hedging Reserve) to find out what we avoid entering in our profit and loss accounts. Thank God the IASB invented hedge accounting, to reduce the valuation to the correct level.

Once you have got past the question of whether or not you are going to hedge, the next issue is figuring out the extent to which you are going to minimise your financial risks. One hundred percent hedging of all balance sheet or off-balance sheet risks strikes us as foolish and inadvisable. Essentially, the treasury is a function of management and this management needs to be applied to hedge part of its exposure and control the remainder, often according to principles and a strategy that have been clearly defined in the internal hedging policy.

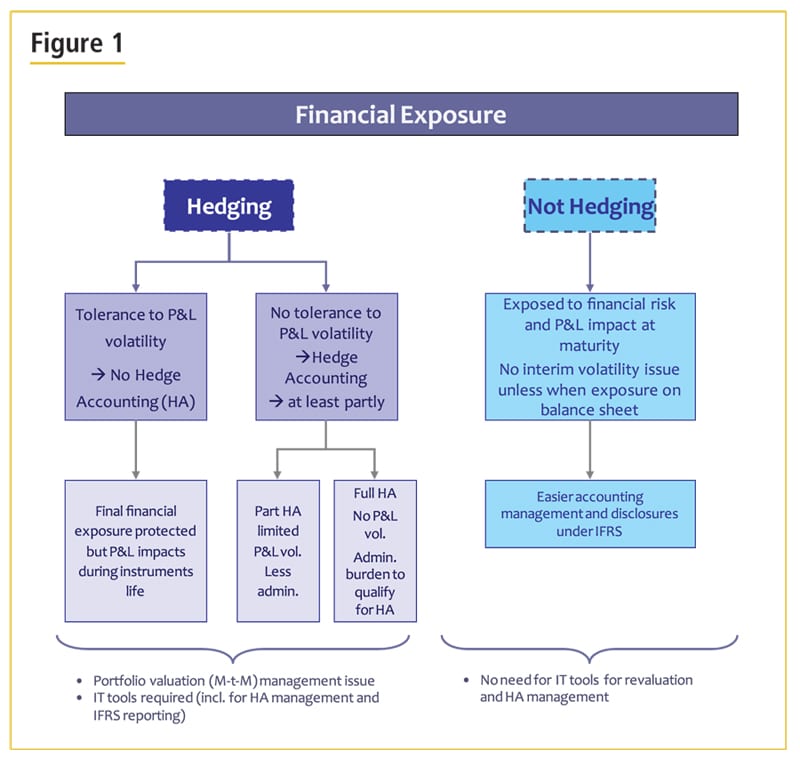

Hedging without applying hedge accounting would seem to be suicidal, as it would amount to not hedging and taking all the impact in the accounts through the ‘mark-to-market’ revaluation of the financial instrument portfolio. Consequently, the issue is how far should hedge accounting be applied? Here too, the treasurer needs to define an intelligent compromise strategy between what is required in terms of hedge accounting and what can, due to its size or lesser impact, remain hedged and re-valued without offsetting to compensate for the accounting impact recorded. Treasurers have also a duty to educate boards and CFOs in order to make them sensitive to risks of inappropriate hedging strategies. [[[PAGE]]]

So-called hedging strategy must always be the subject of written rules and principles that have been clearly transmitted to subsidiaries. However, it needs to remain adaptable in order to respond to changes in the markets and the economic situation. But there is no single ‘one-size-fits-all’ solution. Every policy is different and specific to the company concerned. It needs to be validated by the Audit Committee and reviewed regularly. It should also take the accounting aspect (IFRS) into consideration, based on the hotly contested and unnatural principle initiated by IAS 39 of ‘putting the cart before the horse’. The strategy also needs to determine the precise type of instruments authorised, and this must be done in accordance with the IFRS strategy adopted in order to always remain ‘on the right side’. Finally, it defines the counterparties to be used, as this credit risk is no longer theoretical at all. The company’s hedging strategy will depend on its general culture, its approach to and appetite for risk, and lastly the CFO’s tolerance for the volatility of the financial result. It is dependent on external factors (geography of the group, currencies, long or short positions, profile, natural or economic hedging, etc.), as well as on internal factors as described above. These factors will shape and define the hedging policy. What currencies to sell in? Should the translation risk be covered? Fixing the debt or not? And so on.

Where hedging is concerned, there is a series of pitfalls and errors that must be avoided at all costs in order for it to be effective and appropriate. We are going to try to list some of these in a non-exhaustive fashion.

To be effective, a company needs to design an appropriate hedging policy and to know precisely what it intends to accomplish. It is not as straightforward as it seems. Obviously, everyone wants to protect the business from P&L volatility. The objectives should be aligned to the overall business strategy and be specific as well as quantifiable. The flexibility should not be used to justify the reluctance of the corporate to document a sound hedging strategy. A formal policy is paramount even if viewed as cumbersome and also rather bureaucratic. Without formal rules, there are risks of absence of discipline, transparency in communication to stakeholders and continuity when facing staff turnover. The performance benchmark needs to be measured to determine whether it is effective or not. It also has to be aligned and adapted to strategic objectives targeted. For these metrics, treasurers need to use appropriate state-of-the-art IT tools. The simulations are also important for monitoring closely open positions (e.g., currencies with high differential of interest making hedging ‘expensive’; floating IR portfolio).

Despite the usefulness of FX and IR forecasts issued by investment banks, it can be dangerous to rely too much on simple market views or predictions even from well-known gurus. The hedging process should remain adaptive and gradual to weight possible wrong assumptions. Forecasts are more useful for short-term hedging. The strategy needs solid foundations and principles rather than ‘market-changing’ views. The art is in defining the appropriate ratio level. Another risk is to use over-complex instruments in order to reduce hedging costs. Some features are designed with knock-outs, barriers, corridors, etc. to create so-called ‘zero-cost’ products. [[[PAGE]]]

Treasurers have to use powerful IT tools to revalue these types of products, if dealt. Furthermore, treasurers should have the expertise to de-structure the products in order to price them properly. The more complex a product is, the less transparent it is in terms of pricing. It is essential to align the time horizon of underlying and financial instruments. By hedging short-term, the roll-over of hedging instruments could be expensive and create cash shortfalls. Mismatches are not to be advised. However, (too) long-term hedges could also be expensive (e.g., because of interest rate differentials). Treasurers should always consider cash-flow impacts, especially when hedging non-cash items (e.g., translation risks) or uncertain future exposures. The most complex issue is correlation between exposures and underlying items. When identified, it can reduce the global hedged position, even if not fully perfectly hedged (e.g., CAD and aluminium price, USD and crude oil). When treasurers rely too much on proxy hedges, it can become very dangerous. The hedging strategy needs to be co-ordinated across the group to avoid potential inefficiencies.

These days, for reasons of efficiency, comparability and internal controls, not making use of trading platforms would be a big mistake. Using this type of tool, such as 360T, MyTreasury or FXall, for example, is now established as best practice. These tools permit a straight-through processing (STP) approach and the automation of trade in financial instruments from their initial trading until their final settlement at maturity, including the accounting entries during the life of the product and the ad-hoc transfer instructions. They provide an opportunity to obtain the best prices (real trading market prices online and even better than the indicative pricing displayed on Reuters), but also to obtain a number of reports and statistics that can be useful for internal controls and KPIs/KAIs. They allow operational risks to be significantly reduced, especially when supplemented by a transaction confirmation matching service via MT 300 or Misys CMS. Lastly, they provide a means of putting all one’s banks in open and simultaneous competition in order to allocate the side-business correctly.

The design and the implementation of an effective group FX risk management strategy and policy can be a real challenge for many corporate treasurers. The extreme volatility level experienced on FX markets (especially EUR/USD) over recent months has highlighted the need for carefully considering the FX and interest rate hedging requirements. Then, the question is how sufficient these hedging strategies are in meeting their risk management objectives.

One of the unexpected or unsuspected consequences of the current financial crisis could be a significant increase of FX pricing on longer periods. Dealers are beginning to think more seriously about credit-adjusting the prices quoted on FX derivatives in general. The pressure on banks may force them to adjust pricing up on longer period FX transactions to include the credit risk element. It means that leaving aside swap points and interest differentials, the longer a forward deal, the more expensive it will be. This evolution which we have noticed recently seems to be crystallising now. This is rather surprising for some corporates although it was inevitable, especially after such a deep credit and faith crisis we faced. The solution to reduce the extra cost adjustment applied to FX transactions is to sign an agreement like CSA type (Credit Support Annex) to collateralise bilaterally amounts corresponding to changes in mark-to-market valuation of portfolio of FX transactions made with the bank. The idea, like for margin calls, is to secure the potential (unrealised) loss on portfolio of FX deals revaluation. If the portfolio has a negative change in fair value (lower value compared to inception value), the customer would have to secure this amount with a cash collateral deposit. In the case of a positive change in fair value, the deposit in cash would be made by the bank. Both deposits are remunerated at EONIA rate. Of course, the larger and the more diversified the portfolio, the less collateral would be potentially required.

It is obvious that in case of default (e.g., Lehman Brothers or Kaupthing Bank) the customer can recuperate and compensate, via the deposit, the loss incurred. The bargain would therefore be: does it make sense to reduce cost of hedging FX transactions by collateralisation or not? The more FX transactions dealt, the more the banks used for dealing, the more collateral would possibly have to be immobilised and locked. It could not be considered as cash and cash equivalent according to IAS 7 as pledged to the bank. The return offered will not be as good as the one potentially achieved now with money market funds of prime quality. The CSA will imply review by lawyers and extra legal costs, at least for first contracts to be signed (similar to ISDA schedules). [[[PAGE]]]

Fortunately, limits and margin calls will be managed by the banks’ back-offices. Nevertheless, it will create extra administration for treasury teams. For companies which are cash poor, it has an additional cost, especially when spreads are extremely high, as today. Corporate treasurers could also decide to have recourse to shorter FX transactions rolled-over over time. Again, it will generate extra administration and interim volatility at roll-over dates. That is the price that has to be paid for this type of solution.

The Obama Administration announced in June 2009 a sweeping reform of the financial markets, including a brand new approach of the OTC (over-the-counter) derivative markets (Financial Regulatory Reform: A New Foundation published on 17 June 2009). Meanwhile, the European Commission has issued a consultation document on possible initiatives to enhance the resilience of OTC derivatives markets (Brussels – Commission staff working paper 3/7/9 SEC 2009- 914 / “Ensuring efficient, safe and sound derivatives markets” – COM 2009-332).

The major issue in this reform is its scope. It does not only cover the trading of CDS and CDOs but also plain vanilla hedging instruments (e.g., IRS, currency swaps, etc.). We will all be impacted by such a reform. The aim is to apply new rules to all derivatives, no matter what type of them is traded or priced, regardless of whether they are standardised or customised and it also includes the derivatives to be invented in future. There are no exceptions for simplifying the rules application. Are the ‘standard and classical’ OTC products victims of the excesses of a bunch of them (e.g., CDS and CDOs)? In general, companies use derivatives to reduce exposures and risks and not to trade speculatively.

The direct impact for corporate end-users is obviously the increase of cost of hedging because of margining system, the increased P&L volatility given potential ineffective hedging strategies and unwanted transparency on hedging strategies applied. The OTC reform would lead to higher costs and therefore to increased borrowing and possibly to additional capital requirements. The use of derivative products is essential and legitimate for sound risk management. They are aimed to stabilise prices and mitigate risks. More transparency is certainly a recommended and praiseworthy goal, which can prevent future systemic risks. However, we do not want to negatively impact basic plain vanilla products, the use of which could become ultimately impossible. As always, the excesses from a limited number of persons will penalise the whole derivative user community. The misuse of a couple of sophisticated and complex instruments by traders, together with the weakness of controls by regulators and supervising bodies will eventually impact the vast majority of the users. The cost of repairing the damage to the financial system is extremely high.

To avoid some of the impacts for treasurers, and to avoid being counterproductive, a few financial professional organisations and service providers have recommended excluding derivatives or at least exemption from this reform. We have noticed a real simplification and cleaning of derivative products compared to a couple of years ago, before IAS 39’s stringent provisions on financial instruments.

The risk is that if no exemptions are planned corporations will decrease the use of OTC derivatives, even basic ones. The cost of margining and reporting would be too high compared to benefits. Corporations would need to arrange committed credit facilities to meet central counterparty margin calls, reducing accordingly their total debt capacity. Corporations could suddenly decide not to hedge some financial exposures any longer. The result would be to have unhedged risks and bigger exposures at a time where operations are already affected by the world economic crisis. With IAS 39, some financial hedging decisions were driven by accounting considerations. With the OTC derivative regulations, hedging strategies would be driven by cost and administrative considerations. [[[PAGE]]]

We should admit that so far, corporate treasurers are relatively immune from any financial regulation. The idea with the OTC derivatives regulation would be to standardise derivative instruments (sensu lato) and to require them to be dealt through an exchange with settlement handled through a clearing house or a Central Counter Party (CCP). Interposing a CCP with rules on margining and collateral is designed to reduce counterparty risk (which seems to be an important and useful objective). It also aims to promote fungibility of products and full transparency of markets, to increase legal certainty and to reduce legal risks. Eventually, it enhances operational efficiency by enabling electronic confirmation services and more standardised collateral management processes.

However, after recent bail-outs we could reasonably accept that the default of large multinational banks is rather limited (although not excluded). Furthermore, it remains a delivery risk (which is at the end of the day smaller than a pure credit risk). It should facilitate offsetting and netting down of operations or, if necessary, wind-down. If derivatives (including FX forward and plain vanilla IRS) are quasi ‘burned’ because of the administrative burden and costs they would create, the risk management by non-financial corporations would become extremely difficult. The risk would be to avoid hedging to minimise related costs.

All treasurers would support all regulation measures dedicated to improve controls on financial counterparties and dealers. A better way to reduce risk in the banking sector is certainly not the transfer of constraints and costs to corporations and users. The last thing one would wish is to make hedging impossible, too complicated or expensive for normal business exposures. As usual with such proposed reforms, it impacts several activities and professions, including blue-chip companies, which may suffer for crimes they did not commit. In the modern economy, the banks provide the fuel and corporations are the engines. The risk is to try to purify the fuel while altering the engine.