After the Ballots

How the ‘year of elections’ reshaped treasury priorities

Published: March 21, 2000

Today many large, medium-size, and small companies are looking across borders for new opportunities. Faced already with expanded competition and intensified cost cutting, the business growth of these companies should not be further hampered by the cost and inconveniences of making and receiving payments.

The first decade of the 2000s saw much upheaval and change. Despite the current cloud of the worldwide recession shadowing the global economy, international trade continues to develop;[1] capital flows have reversed direction as investment opportunities have emerged in new economies and in the fast-recovering Asian region; and government and industry-led initiatives have instigated far-reaching changes in regional harmonisation and standardisation of payments. Accordingly, banks and corporations are working through the uncertainties of the current market and trying to position themselves for future growth. In the US market, on which this article focuses, we believe such future expansion will be accomplished only by achieving an optimal capabilities balance among multiple types of cross-border payments.

The complexities of implementing payment practices worldwide pose challenges to firms doing business globally.

Since 2008, the global market has been encumbered by the credit crunch and the crash of the US housing market. Worldwide dampening of market activity and consumer confidence followed, as did a rise in government deficits and borrowing and a decline in the value of the US dollar. As a result, the US and other nations have tended to retrench and turn towards protectionist policies. Fortunately, market forces have diminished the effectiveness of this reaction, and companies increasingly realise that their best chance of improving operations, reducing costs, and building new revenue sources is through foreign trade.

In addition, trends largely in place before the current downturn have fostered change and development in international trade and payments flows. Throughout the 1990s, trade agreements and alliances proliferated, with the rise of Nafta, the European Union, and Mercosur in Latin America; and a reinvigorated ASEAN in South East Asia. Along with this regional cooperation, cross-border standardisation and harmonisation of payments systems were strengthened, notably by the creation of Europe’s Single Euro Payments Area (SEPA), by industry’s still-emerging ISO 20022 payment standards, and by SWIFT initiatives to provide corporations as well as banks access to standard financial communication methodology.[2]

Among mature economies, businesses and the banks that serve them place primary emphasis on generating new revenue and on cutting costs by eliminating obsolete and redundant payment systems.

These developments, plus broad changes in payment preferences – e.g., moving away from paper to electronic transactions – support the rise of a more streamlined and automated payments world, as does the sheer increase in volume. The Boston Consulting Group has forecast that the volume of retail and wholesale cross-border payments worldwide will more than double from 6.9bn transactions in 2008 to 14.5bn transactions in 2016 (CAGR of 10%).[3] But, the complexities of implementing payment practices worldwide pose challenges to firms doing business globally. Harmonisation of payment practices has been difficult to achieve. The forces that encourage it, though generally strong everywhere, proceed at different rates in different regions against different payment systems. For an obvious example, paper cheques have generally declined relative to card payments and direct debits made through the ACH or comparable local clearing systems. However, while the largest declines in paper volumes are exhibited in the US and Canada, a sizeable percentage of US payments are still conducted through cheques, likely accounted for by their persistent use in business-to-business payments.

Credit transfers show similarly mixed results. There has been a slight rise in the use of credit transfers in the US and Canada (representing the increase in wire payments and ACH credit volumes), but Europe, for the most part, demonstrates relative declines, suggesting that card systems and the rise of local clearing systems for debit transactions have outpaced any growth in wires or other credit transactions. [[[PAGE]]]

This same inconsistency in growth patterns and relative areas of focus among economies in different stages of development has impeded creation of a worldwide system and universal network for international payments. Among mature economies, businesses and the banks that serve them place primary emphasis on generating new revenue and on cutting costs by eliminating obsolete and redundant payment systems. Enhancement of client experience and features is also a priority, particularly with the rise of new (and, for banks, non-bank) competitors. Banks in the developed world aim to offer higher straight-through payment rates, better quality, and more dynamic reporting and to integrate payment data with clients’ internal general ledger systems or ERPs. Often, however, these efforts are slowed by global or regional regulatory and standardisation efforts, fraud prevention, and anti-terrorism protection.

In contrast, wholesale payment strategies in developing economies have focused on moving from cash to electronic payments and on developing interfaces with payers, many of them unbanked, through mobile devices or cell phones. Local clearing systems have emerged, but they are often not easily penetrated by payers outside the country. To make global payments into or within these regions, there is little to no reliance on central banking systems. Instead, global private payment networks, such as MasterCard, Visa and even PayPal, or new infrastructures provided by mobile telecommunications, form the bases for interconnectivity.

Multinational corporations have a compelling need to locate untapped revenue opportunities and new labour or sourcing prospects but encounter difficulties when they navigate foreign payments markets and their inherent complexities. Cross-border payments made through traditional methods (cheque, drafts, or wire) put the company at an increased disadvantage against their in-country competitors. The time required to clear an international cheque (often exceeding a month or longer) and the expense associated with wires make it difficult to conduct a lean and efficient business. And, since wire fees are often borne by the beneficiary through deductions from the payment, it is difficult to develop a broad group of satisfied trading partners. However, for companies that make just a few payments into and within foreign countries, international wire transactions do often suffice, and for payments requiring significant remittance data or rapid settlement, wires are essential. But as involvement and activities abroad increase, companies must find ways to pay through local payment systems as well. The key requirements for this capability are:

Since these requirements must be learned and applied according to each region or country’s specifications, it is nearly impossible for any corporation to navigate these areas on its own.

[[[PAGE]]]

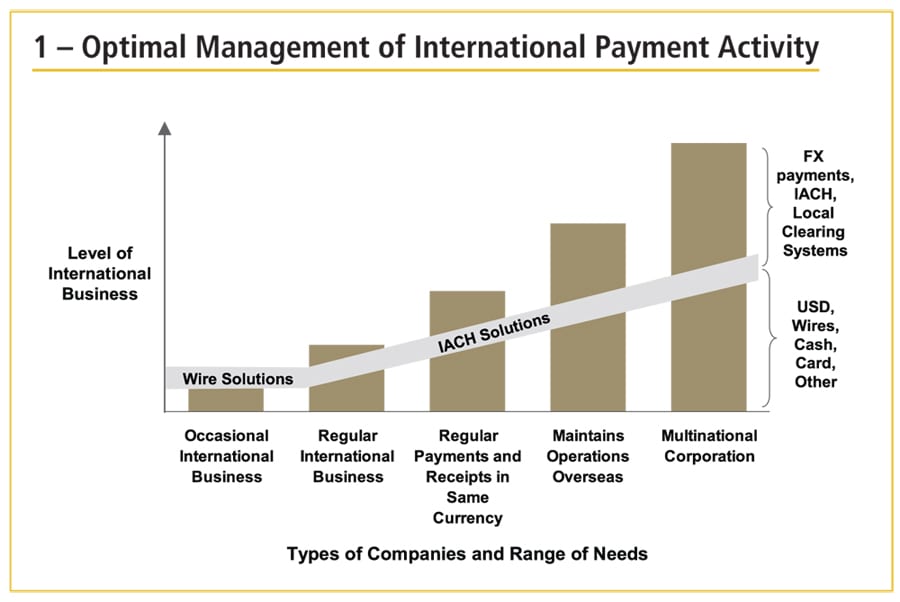

Beyond acquiring a command of local payment systems, deriving a company’s ideal mix among wire, ACH, and card payments involves weighing the costs against the associated advantages. These are determined not only by capital costs but also by the size of the firm, the locations and scope of its operations abroad, and the receiving capabilities of its beneficiaries. For example, a small company that engages a consultant to run a defined project in another country may choose to pay the consultant fees and expenses by wire. Should the project come to require a physical presence in the country, and the consultant is brought onto the company payroll as an employee, it would be more effective to pay the employee and real estate expenses by local ACH. Business operating costs could be funded by purchasing card and local clearing system payments where possible, and by cash and wire in other instances (see Figure 1).

Despite, or perhaps because of, today’s bleak economic outlook, there are countless studies recommending marketing and technology strategies, risk and expense management, and revenue generation schemes. Without robust payment capability, however, a corporation can enact none. In the realm of international business – increasingly a priority for businesses of all sizes – a variety of international payment capability and the knowledge of how, when, and where to use each can be the determinant of survival or demise.

Faced with expanding competition and intensified cost cutting, a corporation’s growth should not be impeded by difficulties in making and receiving payments. Today’s large, medium-size, and small companies are all looking across borders for new opportunities and, accordingly, need to make payments across these borders. However, their degree of involvement and need for top-end services associated with their payments – such as real-time data on transactions and automatic payment reconciliations – vary. BNY Mellon believes the most effective way for companies to meet prerequisites of payments capability is through a relationship with a bank that has direct associations with as many payment networks as possible. These connections can either be through a physical branch presence in each country or through maintenance of international accounts and relationships with local bank correspondents. Optimally, the bank should provide a range of international payment capabilities to meet the evolving needs of the client company’s international activities. Global payment options are improving for savvy companies that are aware of the requirements. 2010 will be the year to gear up and prepare.

Notes

1 World Economic Situation and Prospects, United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2008

2 See Joining SWIFT through SCORE, www.swift.com/corporates/, 2009.

3 “Weathering the Storm, Global Payments 2009” The Boston Consulting Group, March 2009, p. 41.