After the Ballots

How the ‘year of elections’ reshaped treasury priorities

Published: December 01, 2009

For the past year, firms around the world have been intently focused on preserving capital and reducing their reliance on external funding. As a result, managing working capital and accelerating cash conversion cycles have become a key strategic priority. Yet most firms have seen their cash conversion cycle lengthened over the past year. This reflects the difficulty of improving cash conversion cycles during severe economic downturns where firms recognize the need to support important suppliers and customers who may need working capital relief to survive.

To understand the long-term potential of accelerating cash conversion cycles, we undertook an in-depth analysis of 22 working capital-intensive industries, covering 828 of the largest global firms. Our main findings are:

Improving the cash conversion cycle requires firms to collect receivables faster from customers, keep inventories as low as possible, and get better payment terms from vendors. The main benefit of these actions is to reduce the need to fund working capital from bank lines or other external capital sources. An optimized cash conversion cycle enables firms to better manage complex supply chains, strengthen relationships with key vendors, distributors and clients, optimize purchasing processes to achieve larger discounts, and minimize invoicing and collection errors.

We found a highly statistically significant relationship between working capital improvement and improvements in interest coverage ratios.

Because relationship banks help firms collect, invest and pay out cash along the financial supply chain, they can be valuable partners in accelerating the cash conversion cycle, both in streamlining cash processes and extracting liquidity from the supply chain. Few firms have achieved daily visibility into cash positions, accurate cash flow forecasting, and efficient cash repatriation on a global basis. Many firms have fragmented internal processes and too many banks, which are costly and ‘trap’ cash in the system. Finally, many firms have yet to centralize investment processes for managing excess cash. By adopting best practices, we estimate the working capital improvement potential to be up to 30% for the typical large multinational firm, which translates into a 2–3% EPS improvement.

In today’s market, achieving such capital release while boosting earnings is invaluable.

Faced with a prolonged economic slump, firms have preserved capital by sharply curtailing non-essential capital expenditures, by reducing capital distributions at the fastest rate in fifty years1, and by making deep operating cost cuts. Although financial markets have stabilized, most companies face a higher cost of capital and bank lines have become scarcer and more expensive. The turmoil in the commercial paper market has reminded firms of the liquidity risks embedded in short-term financing. [[[PAGE]]]

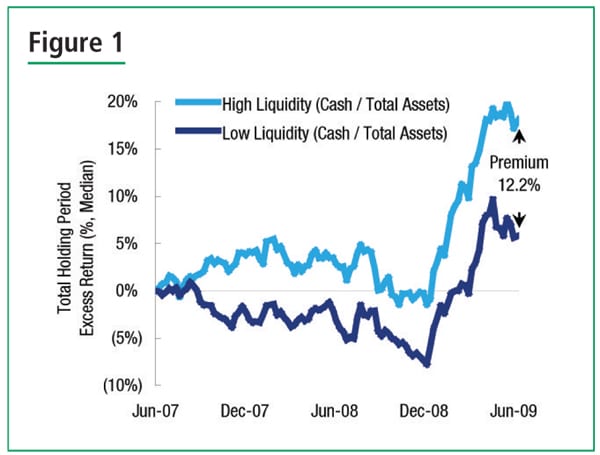

Since the onset of the credit crisis, investors have paid close attention to financial flexibility metrics. Rating agencies and debt holders have been closely tracking corporate liquidity positions for signs that companies might get caught in liquidity traps. After years of paying little attention to balance sheet liquidity, equity investors have paid a large valuation premium for firms with strong liquidity (Figure 1) as well as for firms with higher ability to fund growth internally (Figure 2).[2]

A direct way of controlling and improving liquidity is to manage working capital. For the average S&P 500 non-financial firm, working capital assets (net of cash) account for 25% of total assets and improvements in working capital thus have an immediate and substantial impact on capital usage. Further, the average non-financial firm finances about 60–90% of its working capital with bank lines3, and improvements in working capital thus translate directly into reduced bank line usage.

By accelerating the cash conversion cycle (CCC) – the time it takes from when an order is given to a supplier or a sale is made to a customer, through the manufacturing and sales process, to the time cash is collected from a customer or paid to a supplier – firms can reduce their working capital requirements substantially. Further, by managing liquidity through the cash conversion cycle, firms can deploy and invest cash more efficiently and avoid unnecessary financing costs.

[[[PAGE]]]

Cash conversion cycle — pressures in the short term, opportunities in the medium term

Most firms have seen their cash conversion cycle lengthened over the past year. Among US firms in working capital intensive industries, the median cash conversion cycle increased in both the fourth quarter of 2008 as well as the first quarter of 2009, amounting to an annual median increase of 7 days, or 9%.[4] This deterioration reflects the difficulty of improving cash conversion cycles during severe economic downturns where firms must balance the benefit of reducing their own working capital against the need to support valuable suppliers and customers who may need working capital relief.

In response to these capital pressures, many companies have recently launched working capital improvement initiatives. To understand the long-term potential benefits from such initiatives, we undertook an in-depth analysis of cash conversion cycle trends over the past five years across 22 working capital-intensive industries, covering 828 of the largest firms around the world.[5]

Prior to the credit crisis, abundant and cheap credit meant that the cost of working capital inefficiencies was perceived to be low. In that context, it is not surprising to see that only a quarter of firms improved their cash conversion cycles by more than 25% since 2003, whereas almost half of firms maintained stable cash conversion cycles within ± 25% (Figure 3).

A small portion of firms saw dramatic changes to their working capital (Figure 4):

The 10% of firms who shortened their cash conversion cycle the most over five years (which we refer to as Top CCC Shorteners) shortened their cash conversion cycle by an impressive 81 days, a 50% improvement.

The 10% of firms who suffered the largest working capital deterioration over five years (Top CCC Lengtheners) lengthened their cash conversion cycle by 83 days, a 124% deterioration.

The Top CCC Shorteners/Lengtheners were well distributed across industries, and were similar in terms of size (median 2008 revenue of $4 bn), profitability (median 8% in 2008 net income margin) and credit quality (around BBB+/ A-). The improvement potential (or risk of deterioration) was thus not confined to any particular subgroup of firms. However, the source of improvement in working capital management differed significantly across companies and industries:

Some firms achieved remarkable improvements in their cash collection - the top 10% of firms in terms of improvement in accounts receivables shortened their Days Sales Outstanding by a median of 52 days (Top DSO Shorteners in Figure 5). Other firms were able to substantially extend the payment terms with suppliers — the top 10% of firms in terms of improvement in accounts payable achieved a median of 35 extra days of credit from their suppliers (Top DPO Lengtheners in Figure 6). [[[PAGE]]]

In our experience, we have often seen companies focus on only parts of their working capital, either a specific geography or specific components of the cash conversion cycle, such as days payable. This is not surprising since working capital requirements are an outcome of decisions made in myriad parts of the firm — across business divisions, procurement, manufacturing, sales, credit and collection, treasury and controllers — making firm-wide efforts difficult to implement. As improving working capital has become a corporate priority, we have seen more firms adopt a company-wide approach focusing on the entire conversion cycle. This holistic approach is reflective of how the Top CCC Shorteners achieved their improvements, namely by improving on all three aspects of the cycle from accounts payable, inventories, to accounts receivables. Substantial improvement potential persists across industries

Substantial improvement potential persists across industries

Industries with complex supply chains and global operations typically have the largest potential for working capital savings. But even within industries, there is a surprising degree of disparity in working capital practices of firms vis-à-vis their industry peers. Simple industry benchmarking reveals substantial improvement potential across all industries: Figure 7 shows the difference in cash conversion cycles between the bottom quartile, median, and upper quartile of close peers across select working capital-intensive industries as of the end of 2008. Across industries, there is a 31% difference between the cash conversion cycle of the 75 percentile firm and the median firm, and a 37% difference between the median and the 25 percentile firm.

By adopting best-in-class practices, our experience from assisting clients on working capital initiatives suggests that the typical multinational could reduce its working capital financing requirement by up to 30%. Such an improvement is equivalent to moving up one quartile in relative cash conversion cycles compared to industry peers (Figure 7), and typically translates into an EPS improvement of 2–3%. These improvement estimates are in line with the experiences of management consultant firms like Bain & Company and Boston Consulting Group who estimate a 30–40% working capital reduction potential from their improvement initiatives. [[[PAGE]]]

Large upside from optimizing working capital

Large upside from optimizing working capital The most significant benefit from accelerating the cash conversion cycle is to reduce the need to fund working capital from bank lines or other external capital sources. But the benefits extend beyond the savings in financing costs. An optimized cash conversion cycle enables firms to better manage complex supply chains, strengthen relationships with key vendors, distributors and clients, optimize external purchasing processes to achieve larger discounts, and minimize invoicing and collection errors.

Skeptics sometimes question whether these tactical benefits contribute meaningfully to the larger strategic objectives of driving growth, improving margins and creating shareholder value. For large, complex multinationals whose financial results are driven by multiple forces, the question is whether working capital improvements might be drowned out. Our experience suggests otherwise — accelerating the cash conversion cycle has enabled firms to substantially boost return on invested capital, increase capex, outgrow peers, and deliver substantial outperformance in shareholder returns.

To quantify these benefits, we conducted an in-depth statistical analysis to determine whether long-term improvements in cash conversion cycles correlate with improvements in financial performance when controlling for other factors such as growth, profitability, size, interest coverage and credit quality. Since we are interested in firm-specific improvements as opposed to industry-wide working capital and profitability trends, we looked at how improvements in relative cash conversion cycle performance could explain improvements in relative return on invested capital. Over the 2004–2009 period, we compared each firm to its industry peers to assess whether the relative working capital efficiency and return on invested capital had changed.

We found substantial economic benefit for firms who improved their cash conversion cycle (Figure 8). Firms whose relative cash cycle improved by one quartile compared to peers saw their return on invested capital increase by 84bps.[6] The impact was even greater for firms with the weakest profitability — firms in the bottom profitability decile who managed to improve their relative cash cycle by one quartile reaped an average improvement in ROIC of 221bps. As expected, the benefits were particularly pronounced for high-yield firms facing higher funding costs than for investment-grade firms (98bps versus 78bps).

Figure 9 shows the economic benefit across select industries. While the median ROIC improvement potential was 84bps, certain low-margin industries with complex supply chains like textile manufacturers, retailers, and the auto industry had even higher improvements in ROIC.

Benefits extend beyond reduced financing cost

The most direct driver of the ROIC improvement is the reduction in necessary financing needs. Not surprisingly, therefore, we found a highly statistically significant relationship between working capital improvement and improvements in interest coverage ratios.

Yet firms that achieved the largest working capital improvements enjoyed additional benefits relating to capex intensity, sales and earnings growth, and valuation metrics:

Capex intensity One of the main benefits is the release of capital which can be deployed into growing the business. Figure 10 shows the dramatic difference in capex growth between Top CCC Shorteners and Lengtheners: about 30% of the Top CCC Shorteners increased their capex in the following year by more than 50% compared to only 5% of the Top CCC Lengtheners.

Sales and earnings growth A common concern is that shortening the cash conversion cycle might impede a firm’s ability to maintain revenues, and that firms thus should sacrifice their cash conversion cycle in order to grow sales. Undoubtedly, it occasionally makes sense to selectively offer key vendors or suppliers more favorable terms to protect the supply chain or keep key customers. But Figure 11 clearly shows that it is possible to simultaneously improve working capital and post strong revenue and earnings growth. The Top CCC Shorteners consistently outgrew the Top CCC Lengtheners on both the top and bottom line (a 700bps CAGR difference over a five-year period).

Equity valuation. The ultimate testament to the value creation potential from improving working capital efficiency is shown in Figure 13 which displays the cumulative excess return, controlling for market-wide movements and individual company risk. Top CCC Shorteners exhibited an impressive 30% excess stock return, whereas the Top CCC Lengtheners began exhibiting negative excess return starting in 2007, and a substantial underperformance compared to the CCC Shorteners.

Working capital and operational excellence

The ROIC benefits shown in Figures 8 and 9 can be directly traced to working capital improvement efforts since our statistical analysis controls for other relevant factors. The outsized capex intensity, growth rate, margin and share price performance associated with the Top CCC Shorteners shown in the previous four graphs — while correlated — are not necessarily driven only by working capital improvements. In our judgment, this correlation reflects a commitment to overall operating excellence among the Top CCC Shorteners. Large improvements in working capital can only be achieved through a coordinated effort across business functions including treasury, procurement, manufacturing and sales. Firms that have a strong culture of operating excellence in the overall business are more likely to also have a strong handle on the operating aspects of working capital management, and the strong correlations are therefore not surprising.

In its simplest form, improving the cash conversion cycle requires firms to collect cash faster from customers, keep inventories as low as possible, improve investment returns, and get better payment terms from vendors. But when there are thousands of suppliers, distributors and customers spread across the world (many of which may have limited access to credit), unilaterally delaying supplier payments or trying to forcibly shorten days receivables carries significant business risk. What is needed, therefore, is a thoughtful approach that eliminates inefficiencies across the cycle without unduly damaging the manufacturing process, vendor relationships, or sales prospects.

Since working capital is a function of decisions made across the firm, improvements require a clear understanding of the drivers of working capital performance, finding inefficiencies as cash travels through the system, and agreeing on how to measure and reward success. A typical working capital initiative would focus on standardizing invoicing and payment terms per customer or supplier segment while ensuring that they are aligned with industry practices, closely tracking payment status and customer credit limits, and shortening the dunning process including establishing a transparent schedule of escalating payment demands. Successful inventory initiatives start with a thorough analysis of customer demand and supplier behavior which enables firms to optimize their safety-stock levels. Additionally, reducing product complexity enables significant reductions in required inventory levels.

How relationship banks can help firms manage working capital

Because relationship banks help firms collect, invest and pay out cash along the financial supply chain, they are critical partners in accelerating the cash conversion cycle. Figure 14 illustrates the three broad areas where relationship banks are involved in the financial supply chain of firms: Procure to Pay (associated with accounts payable), Order to Cash (associated with accounts receivable) and Treasury and Cash Management Processes.

[[[PAGE]]]

Procure to Pay

This refers to the collective set of processes that begins with issuance of purchase orders to suppliers and ends with payment to these suppliers. Many companies have procurement processes that are managed at a business line or subsidiary level across many markets. Consequently, these processes are manual, paper-based, and fragmented. Centralizing internal processes and banking arrangements — for example, by implementing shared service centers — and investing in technology generates several benefits:

The combination of centralization and technology can have powerful impacts. For example, expenditures can be assessed to ensure spend policy compliance on an ongoing basis, rather than after the fact. Also, firms can make better decisions as to when and where to make use of vendor early pay invoice discounts.

Additionally, firms in a stronger financial position than their vendors can sponsor supplier financing programs through a relationship bank partner. Suppliers selected for the program take advantage of the creditworthiness of their buyer to access relatively cheaper financing through the bank. Export Credit Agency financing programs supported by governments in many countries have further helped increase banks’ appetite to provide such financing. As a result, the buyer can receive extended payment terms. The lower-cost financing provided to vendors also strengthens business relationships for the longer term — having the buyer’s relationship bank in the chain provides greater comfort to the vendors than traditional, one-off, factoring programs. This can feed back into more advantageous sourcing costs for the buyer. Hence, a supplier financing program has the potential to transform what would otherwise be difficult discussions between a buyer and their vendors on better payment terms into a win-win outcome for all.  Order to Cash

Order to Cash

Order to Cash refers to processes on the revenue generation side, from customer order fulfillment to the receipt of cash and application to outstanding receivables. As the number of customers and distributors involved in cross-border trade has increased, many companies have ended up with processes that are even more fragmented than on the procurement side. By centralizing and automating this process, firms enjoy several benefits:

[[[PAGE]]]

Also, through receivables portfolio financing and distribution financing programs, firms can support sales growth without extending the cash conversion cycle. The seller partners with a relationship bank, which purchases selected customer accounts receivables on an ongoing basis. The bank also provides automated servicing and reporting tools which, for example, facilitates credit risk management. The seller may also give its customers more advantageous payment terms, in turn enabling them to extend their days payable outstanding to the seller.

The use of financial intermediaries can create a win-win situation and strengthen relationships in the supply chain. The seller is usually able to increase sales to existing customers without maintaining and financing more and more receivables on its balance sheet. The related technology tools also enable the seller to better monitor and mitigate credit risks. The seller can also offer its customers more competitive payment terms, which enables customers to continue to buy using the liquidity gained between purchase and payment.  Treasury management

Treasury management

Procure to pay and order to cash processes fundamentally impact the predictability, timing, and mix of cash inflows and outflows. With responsibility for the firm’s financing, risk mitigation, and safeguarding of cash reserves, treasury departments should take the lead in driving working capital improvement initiatives. As a first step, treasury will need to embed ‘cash flow thinking’ into the responsibilities and incentives of business functions across the firm. But treasury should also look inward to assess the adequacy of its own operations.

Treasuries have typically centralized decisions relating to corporate finance, capital markets activity, and FX hedging. Cash management, on the other hand, was often regarded as a tactical function, best managed locally or regionally. With the increasing importance of cash management, many treasuries are moving toward a more centralized approach to cash management. However, many sub-optimal practices persist. Many firms have:

As a consequence, firms have pools of liquidity ‘trapped’ within the system and struggle with monitoring and mitigating FX, interest rate, and counterparty credit risks. To overcome these inefficiencies, treasury departments should work with global banking partners to consolidate financial institution operating relationships, rationalize and integrate internal cash management processes, and use bank and internal technology platforms to support global cash visibility and centralization.

Notes:

1 See our previous report ‘To Cut or Continue – the Dividend Decision for 2009’, Citi Financial Strategy Group, March 2009.

2 We tracked the share price performance of the non-financial companies in the S&P/Citi PMI Global Index for which data was available. In Figure 1, each company was classified as having high or low liquidity based on their cash holdings (as a percentage of assets) relative to their industry peers. Similar approach used for Figure 2. See also our previous report ‘Navigating Troubled Waters – What the Credit Market Turmoil Means for Corporations’, Citi Financial Strategy Group, October 2008.

3 Estimate based on a subset of three average sized companies in the S&P 500 across 10 industries. Bank lines do not include CP backstop facilities.

4 See list of industries in Figure 7. Certain industries were particularly hard hit, including semiconductors (28 days increase), metals & mining (29 days’ increase), autos (26 days’ increase), homebuilding and household goods (22 days’ increase), textiles and apparel (ten days’ increase) and chemicals (nine days’ increase). The largest improvement was in the personal & household products industry where the average cycle shortened by two days.

5 These 828 firms in the 22 working capital intensive industries were selected based on their inclusion in the S&P/Citi PMI Global Index (See Figure 7).

6 As discussed in the prior section, a one quartile improvement constitutes a large, but realistic objective for many companies.