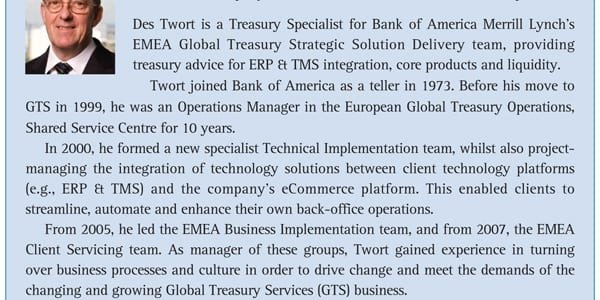

by Des Twort, EMEA Treasury Specialist, Bank of America Merrill Lynch

One of treasurers’ most important, and often most frustrating, tasks is to track down the location of their company’s cash, in any subsidiary and bank account across the world, and then to take control of it. This is not merely an intellectual exercise. As the effects of ongoing liquidity constraints and economic fragility continue to affect companies of all sizes, maximising the use of every dollar can literally make the difference between survival and ruin.

A strategic need for visibility

Due to frequent mergers and acquisitions, in many companies, the trend towards globalisation has been accelerated. This often results in bank relationships, accounts and cash management structures becoming fragmented, particularly in decentralised organisations where newly acquired subsidiaries retain their operational independence. Consequently, even if treasury has efficient technology in place, complex organisational structures, diverse technical environments in different parts of the group and dispersal of cash across multiple bank accounts globally can hamper the most robust efforts to centralise and manage liquidity at a group level. However, when cash is not being used for the good of the business overall, strategic and competitive opportunities can be lost, such as reducing borrowings, maintaining working capital levels, optimising investment income and making strategic investments.

An operational need for visibility

Operationally, lack of visibility over bank account information also brings challenges. Unreconciled transactions can mount up, reducing the amount of available cash and creating accounting difficulties. Customer credit limits may incorrectly be shown as fully-utilised, damaging customer relationships and preventing repeat business. Lack of available cash or limitations in accounts payable processes may also result in suppliers being paid late, which can again erode relationships and jeopardise the stability of the financial supply chain. With many smaller businesses particularly vulnerable as a result of ongoing liquidity constraints, predictable cash flow is key; and without timely invoice settlement, the risk of key suppliers going out of business can be substantial.

A multi-faceted approach

Despite the challenges, obtaining timely bank account balance and transaction details with complete and consistent transaction data is a challenge worth pursuing. As every corporation differs in scale – complexity, technological capabilities, business focus, geographic reach and culture – it is impossible to envisage that a single solution could be used by such a diverse community to achieve visibility and control of group cash. Bank connectivity is one corner piece in the financial systems jigsaw, but equally, the right connectivity channel is not a golden ticket to cash visibility. While many larger, more complex corporations with global, multi-banked connectivity requirements are increasingly selecting SWIFTNet as their communication channel, other companies that may be smaller, less complex, or have fewer banking relationships, may find that banks’ proprietary host-to-host (including integrated ERP connections) or web-based electronic banking systems are more suited to their needs. The same applies to file formats. As SEPA instruments are based on XML ISO 20022 standards, this has been a catalyst for many larger companies to introduce standard formats for payments across their business. There are still some challenges to ISO 20022 adoption, but these are likely to be relatively short-lived. For example, for a standard to be effective it must rely on widespread adoption. Some banks have yet to adopt ISO 20022 consistently, but this is changing and the standard is increasingly enabling larger, more complex corporations in particular to achieve more coherent payment processes. For firms without the same degree of format fragmentation or payments diversity however, there may not be sufficient cost or efficiency benefit to move from existing formats.

Sign up for free to read the full article

Register Login with LinkedInAlready have an account?

Login

Download our Free Treasury App for mobile and tablet to read articles – no log in required.

Download Version Download Version